Women looking with desire at men’s bodies seems to be making something of a comeback as part of our engagement with film and television.

I’ve been doing a bit of lustful gazing myself lately. Recently, I watched and enjoyed the BBC series Poldark. It stars the ruggedly gorgeous Irish actor Aidan Turner as the central character Ross Poldark. Poldark is a passionate, moody, complicated, socially conscious and loyal man and the series is polished, beautifully scripted and very well acted by all involved. And yet to the detriment, perhaps, of all these other positives, much of the media’s focus has been on the beauty of Turner’s face and body. I’m as guilty as the mainstream media for expressing an almost hysterical response to this man’s dark sex appeal – having recommended the series to other people my recommendation has invariably included a comment on the heat generated by Turner’s body on screen.

I felt bad about this. For maybe 20 seconds. I considered the possibility that by empowering my ‘female gaze’ I was participating in some kind of reverse sexism. Maybe the fact that I’m not sure if I am doing this is part of the problem. But then again it feels like I’m being given permission to look, even being encouraged to do so. The series was created and written by a woman, Debbie Horsfield, adapted from Winston Graham’s beloved series of novels. Horsfield has crafted images that appeal to a straight female gaze – feisty female characters plus a Byronic hero you can’t take your eyes off. I loved many things about Poldark but I’d be a liar if I said the thing I loved most was something other than getting to watch Turner in various poses (including his now famous shirtless scything which has rightly surpassed Colin Firth’s wet shirt in Pride and Prejudice for visual stimulation). One of the pleasures of consuming most BBC or other period dramas is not only the attractiveness of their locations and costumes, but also the attractiveness of the bodies (male and female) that are placed into those locations and costumes. There are, undeniably, a whole host of intimate pleasures bound up with the act of looking at even the most heavily clothed bodies.

In film as it is in television. The most constant of the very many pleasures of film are its visual pleasures.

Strangely, this has reminded of a very different screen first for me – my first look at Richard Gere in Paul Schrader’s American Gigolo (1980).

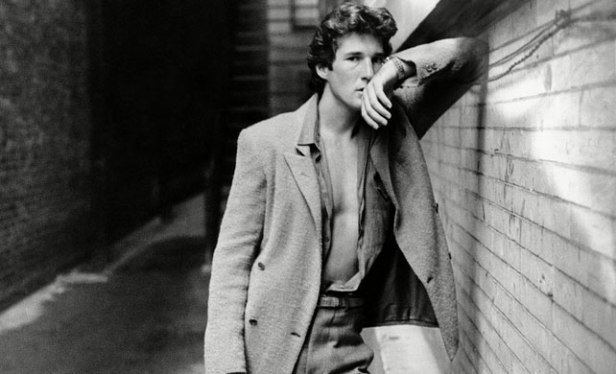

Gere came to prominence in the late 1970s and early 1980s in roles that positioned him as a figure to be looked at. And Schrader’s film played a massive part in shaping this aspect of Gere’s star persona. In American Gigolo, he’s cool and tender, seductive and low-key. Becoming Julian Kaye, Gere found a role wholly modulated for his understatement, smooth moves and honeyed voice. It’s a role in which he demands to be looked at.

Julian is, as the film’s title makes clear, a gigolo. Working as a high paid male escort in Los Angeles, Julian has expensive tastes and aspirations to better himself. He lives in a world of superficial surfaces, all beautiful, including his own. A relationship with Michelle (Lauren Hutton), the unhappy wife of a politician, pushes him out of this routine and sullies the surface sheen of his life.

What’s most striking about American Gigolo is the way Gere’s body seems to be displayed explicitly for the audience to take pleasure in looking at it. Whether shopping for Armani or exercising in his underwear in his apartment or revealing all of himself in the dappled light by his window in a rare exhibition of full-frontal nudity (albeit, from a distance and without photographic emphasis), he seems aware of his appeal and yet simultaneously indifferent to it.

But there are two scenes that stand out as exemplars of Schrader’s play with Gere’s body and appeal in American Gigolo.

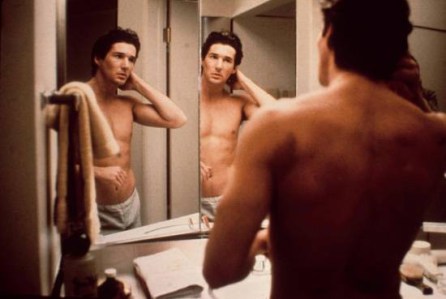

In the first, Schrader encourages our voyeurism and the spectacle of both Julian’s consumption of beautiful things and our consumption of his beauty. He’s preparing for his night out, preening himself, unselfconsciously, as he lays out combinations of shirts and ties before dressing. He’s not aware we are watching as he sings along with Smokey Robinson & The Miracles’ ‘The Love I Saw in You Was Just a Mirage’. It’s a narcissistic moment, but also a private one. It can also be argued that it’s a characteristically feminine moment – something we imagine women often do, something we rarely see as part of a performance of masculinity.

In this private moment, Julian performs for no one but himself. He’s thinking, dreaming and imagining himself in these various colour combinations. But he’s also performing for our visual pleasure. Seeming to add nothing to the film’s narrative drive this scene quietly and slowly builds layers of character and in turn a new way of engaging with the male body on screen that, as the decade would continue, would become a more striking anomaly of American film manhood.

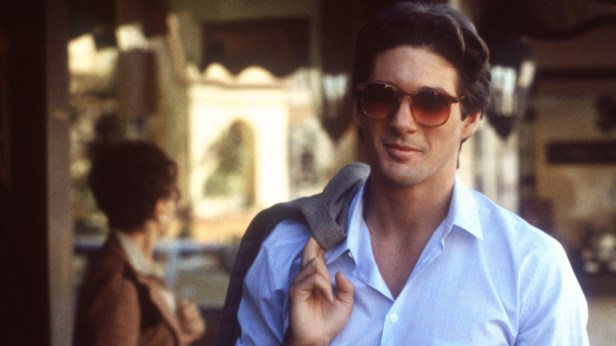

The second scene extends this focus on the idea that Julian’s body is displayed for our pleasure. And here, in a public space he seems to perform, consciously, for the camera and our lustful eyes. The camera follows Julian as he walks down the street. It’s a sunny day and he’s cool in jeans and a shirt, sweater flung over his shoulder, sunglasses on, and a slender smile on his face indicating contentment with life in that moment and with himself. He swaggers – gone is the unselfconsciousness he demonstrated in the privacy of his own home. Michelle is following him. He knows it and enjoying the attention his smile widens. And we are following him too. Schrader extends this sequence longer than seems narratively necessary. But then Gere has a great, silky walk so why wouldn’t you want to watch it for as long as you can. Schrader seems to understand this and gives us what we desire.

Gere is not an actor with tremendous range but he is an actor with screen presence – a star quality that outstrips talent. In the 70s and 80s he was labeled a sex symbol and seemed to revel in this status. Much has been written about Gere’s ability to convey narcissism and an indolence bordering on laziness as they key elements of his star persona. And indeed, in his best and most memorable work – Looking for Mr Goodbar (1977, Richard Brooks), Days of Heaven (1978, Terrence Malick) and An Officer and a Gentleman (1982, Taylor Hackford) – Gere’s energy is focused inward, on himself, certainly more than it is on his co-stars. You can even see this in his most iconic, later role as millionaire businessman Edward Lewis in Pretty Woman (1990, Garry Marshall).

But Gere’s masculinity, as exemplified in American Gigolo, might be best discussed as a counterpoint (alongside Mickey Rourke’s, for that matter) to the dominant narrative shaped in the 1980s by the patriotic hits taken by the hard-bodied muscularity of men like John Rambo (Sylvester Stallone) and Die Hard’s John McClane (Bruce Willis). In contrast to these indefatigable action bodies, Gere makes a veritable virtue of interiority, sensuality, and vulnerability. And in doing so encourages us to look closely and openly with desire at a softer masculinity that embraces the feminine without trying to destroy it.

I believe Gere took his inspiration from Alain Delon. It was reported somewhere that he has a full sized poster of AD in his flat. I’d say he did the right thing. Delon is the unsurpassed epitome of the modern Adonis – beautiful, complex, sensual, vulnerable, narcissistic, introverted, restless. I love your blog about him.

Delon is definitely an Adonis. Thanks for reading and your lovely comments.