This piece was originally published as part of my Critics Campus coverage for the 2014 Melbourne International Film Festival.

A long, sunbaked lunch is the philosophical centerpiece of Richard Linklater’s Before Midnight (2013). As Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Celine (Julie Delpy) finish their meal they listen carefully to an older woman share her view of life: “We appear and we disappear. We are so important to some, but we are just passing through.”

Jesse and Celine recognise the essential truth in this line. They’ve voiced it themselves many times, when they first met each other in Before Sunrise (1995) and nine years later when they reconnected in Before Sunset (2004). Jesse pleaded with Celine to get off her Paris bound train and wander around Vienna with him in Before Sunrise by asking her to project herself into the future, “Jump ahead 10, 20 years”; to imagine the regret she’ll feel if she doesn’t go with him. Who knew, at that point, that jumping ahead in nearly those exact increments is what Linklater would also ask of his audience? We jump ahead nine years to Paris where Jesse once again tries to draw out time for as long as he can. Life, he says, is “actually happening”; an acknowledgment echoed and questioned several years later in Before Midnight when he asks, “Is this really my life? Is this happening now?”

It is. Life happens in the small moments. While we are walking and talking, sitting on a train, reading a book, catching a glimpse of someone, sharing a meal, falling in love. These are the little earthquakes that shake us up when we least expect them to. These are the moments that seize us and make and shape a life.

Linklater’s Before series is sparked by this metaphysical current, by his alertness to the transitory and ephemeral nature of existence and the way we interact with each other. With these films, in which we witness not only Jesse and Celine age together but also the actors who have played them now for nearly 20 years, real time takes representational form, even though technically we know we are watching a fiction. Linklater doesn’t so much seize and freeze time as let his characters be seized by it, while his camera observes them living within the boundaries of the screen.

In a video essay created by Kogonada for Sight & Sound in November 2013 (http://vimeo.com/81047160), Linklater explains that how we see time and whether it can be controlled are questions he sees as the “building blocks of cinema”. They are certainly questions he has grappled with throughout much of his filmmaking career (Tape, Waking Life and the Before films) and perhaps nowhere more playfully and profoundly than with Boyhood his latest “time sculpture”.

Boyhood was filmed over a period of 12 years, in short annual shoots with the same group of actors in the main roles. Characters and the actors that play them grow up right in front of us, which is always riveting to behold. Boyhood’s narrative beats to the ticking of a clock that just happens to condense 12 years into 165 minutes. And while the broad concept behind Boyhood is not entirely unique – think about François Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel series, starting with The 400 Blows, or Michael Winterbottom’s prison drama Everyday shot over a five-year period or Michael Apted’s sprawling Up series for television – it is distinctive for concentrating time’s passing into one singular art product.

Watching Mason (Ellar Coltrane) grow from a cherubic six-year-old to a thoughtful young man leaving for college is an investment. By the end of those 165 minutes my relationship with Mason was an emotionally intense one. I’ve felt the same way watching Jesse and Celine evolve over the past two decades. I’ve grown up with them. I’m roughly their age. Their story feels like my story. I’ve invested both my time and my heart in wanting nothing but the best for them.

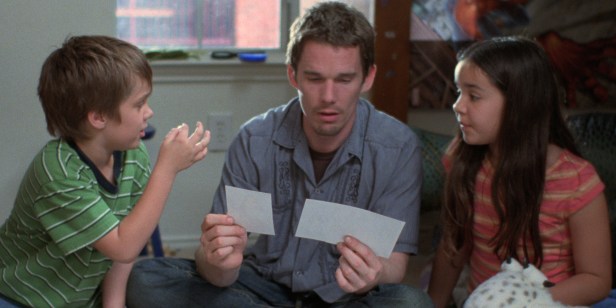

Time is always passing in cinema, always moving forward, never still, never truly captured within the frame. Time is a series of moments or shots carefully, or chaotically, assembled one upon the other to create a story. Mason’s story is a collection of moments that are extraordinary for their ordinariness. Mason gets a haircut he hates, rides his bike, goes camping with his dad Mason Sr (Ethan Hawke), fights regularly with his sister Samantha (Lorelei Linklater), takes photographs, confesses to his mum Olivia (Patricia Arquette) that he’s a little drunk, falls in love, has his heart broken and leaves for college. Much happens in between. It’s the “poetry of day-to-day life” as Jesse called it in Before Sunrise, no dramatic plot-points or events. It’s exquisite in its simplicity, and ultimately, magnificent in its profundity.

Long-takes (also frequently used in Before Sunrise, Sunset and Midnight) allow characters to simply go about the business of living. Each of these takes – showing characters around a table eating, in the classroom, in conversation – makes each scene feel present and alive. Situations unfold and we simply sit and observe. Mason and his family are living in the now and that’s exactly where Linklater places us alongside them.

In Boyhood’s final scene Mason has a conversation with a new college friend, Nicole, which seems to pick up where Jesse and Celine left off at the close of Before Midnight. She suggests that in living, we don’t seize the moment, “it’s the other way around. You know, like the moment seizes us.” Mason agrees, “It’s like always right now.” Perhaps this exchange drives Linklater’s thesis too obviously through what has just transpired, but like Jesse and Celine before them, Mason and Nicole are grappling with nothing less than the question of what it means to be present in the world, for which there are never any simple answers, and for this they (and Linklater) are forgiven.

In the end, the narrative Linklater has shaped can’t ever contain Mason’s entire story. Like Antoine Doinel’s tale, it, and he, has a life that extends beyond the frame and into our imaginations. Linklater sculpts an intimate space that seizes us too. As Mason leaves for college, Olivia breaks down and laments the passing of time: “I just thought there’d be more.” I felt the same way when Boyhood came to an end. I thought there’d be more. I wanted more. I still do.

Loved this post. Absolutely on point!

And I think it’s an interesting subversion to the mantra of Dead Poets Society . I’m not sure what the latin is for “the moment seizing us” but I’ll have to find out!

Thanks Stephen. It’s difficult to watch that scene without thinking of Dead Poets Society, isn’t it. Two different, equally interesting life philosophies.

Yeah…dead poet society comes in mind!!!

Lovely piece. Time is also a string of moments strung together!

Great, great post. I have been following the Jesse and Celine movies since I was 19. They are wonderful. Boyhood was a cool concept, but I was expecting… more. I ‘as emotionally invested in this film as I was for the ‘Before’ movies. Cheers.

That’s the power of a great story, it leaves you wanting more. That too is what makes a great life, you leave wanting more. It’s a life that is seized by moments you long to seize forever but alas moments are passing, they flow in the current of a simple stream and never return. But it’s okay because the waters are still plenty and still flowing and many more seizing moments will wrap them selves around you. Be still. They will seize you without ceasing.

Wonderful post!! Thank you for sharing!

I caught both of the before series and just love it! Sometimes u wonder if fate works in such wondrous ways in real life. Lovely extract of the sentimental moments!

Thanks for reading.

I loved this film. Just watched it 2 days back. I am amazed that how awesome a director is this man. Will miss the before sunrise series.

I’m hopeful for another instalment in ten or so years time.

I agree whole-heartedly. This film left me wanting more. I saw it a month ago, and can’t recall ever thinking about a film this much after having seen it. The intimacy into the lives of the characters was mesmerizing.

Thanks for your comment.

I recently saw Boyhood, and I wasn’t disappointed. What a fantastic, deep concept–especially considering what it took to make such a movie. I will be on the lookout for the other films you’ve mentioned here.

PS “Why don’t you say goodbye to that little horseshit attitude, okay, because we’re not taking that in the car.”

Thanks Anthony. You should definitely see those other films.

PS Great quote!

Loved it!

I am blown away with your writing it read like liquid. Thank you I have found a reading home

Thanks so much – that’s a lovely thing to say.

I loved your piece! It’s wonderful how Rich’s movies have reached out in real lives and bring people together. I have always answered for questions regarding my thoughts on best movie or favorite movie one of the ‘Before’ movies. And when that answer is in agreement it tends to starts a conversation that leads to a kind of bonding. If they value the movies the way you and I and the other readers value it, I feel connected. Thank you for sharing such a beautiful piece!

Thanks for reading and for your lovely, generous comment. I do feel, quite strongly, that cinema connects people in ways that are often beyond words.

Very true words. Such an amazing summary

Thanks – I’m glad you connected with what I’ve written.

Great writing. A great read. Inspiring me to seek out those films.