‘It has more style than substance …’

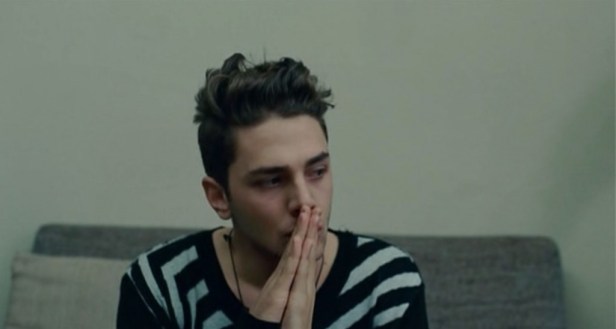

For every piece of writing that praises writer/ director/ editor/ costume designer and sometime actor, Xavier Dolan’s films, you’ll also read pieces that contain a version of my opening line, that disparage them as showy, aesthetic experiments with little narrative weight.

I’ve seen two of Dolan’s five films (with the rest to come later this month when they screen at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image from 18 September to 5 October) and I couldn’t disagree with this valuation more.

It started for me with Dolan’s fifth film, Mommy – which tied for the Jury Prize with Jean-Luc Godard’s Adieu au Langage (Goodbye to Language) at Cannes this year and is currently screening at TIFF – which I viewed at the Melbourne International Film Festival last month. As I’ve written already here, there had been a tremendous, genuine buzz about this film from almost everyone I talked to throughout the festival so when an extra screening was announced I changed my plans and booked my seat. It may sound exaggerated but I walked out of that screening a different person than I was when I walked in. The ground beneath me had shifted. This was my first Dolan film and it was a seismic discovery for me. I hadn’t had an experience like it in quite some time.

I was keen for more. Not long after, I bought myself a copy of Heartbeats (Les Amours Imaginaires), Dolan’s second film, in which he also has a key role. It was released in 2010 when he was just 21.

I probably shouldn’t be writing about Dolan’s work until I’ve seen his first film, I Killed My Mother (2009), his third, Laurence Anyways (2012) and the fourth, Tom at the Farm (2013). But I feel like my experience watching both Mommy and Heartbeats has given me license to effuse grandly about what I believe to be the very particular alchemy in his films that makes them so affecting and magnetic.

Watching just two of Dolan’s films has been enough for me to conclude that his cinema is one big, throbbing organ of emotion and empathy. I challenge you to watch his films and feel nothing. Undeniably, Dolan succeeds in this seduction in part because of his extraordinary style and a skilfully developing mastery of the filmmaker’s toolbox. There’s colour, music, faces, interesting framing and an overall saturation of gorgeous feeling when all of these elements are combined. Both films look great, as I’m sure his other three do too. But there’s more. There is certainly substance created by this style, by his enthusiasm to experiment with the form itself. It’s impossible to write him off, and you shouldn’t – Dolan is giving us a new way of looking at images, which reminds us that film language is a constantly evolving lexicon.

In interviews, Dolan has often explained how little interest he has in intellectualising the process of filmmaking (another reason he fervently rejects comparisons to Godard, and I’d say he’s more like Truffaut, if comparisons with the New Wave need to be made). For Dolan, film is a medium for capturing and conveying emotional experiences above all else. He wants you to watch his films with your eyes and ears, but mostly with your hearts.

I’m happy to say my heart was fully engaged watching Mommy.

Set in a working class Québec suburb, Mommy introduces us to a widow, Diane ‘Die’ Després (Anne Dorval) about to welcome home her 15-year-old son Steve (Antoine-Olivier Pilon) after a stint in juvenile detention, where he ended his stay by starting a fire that has seriously injured another boy. Steve suffers from ADHD and violent tendencies. He’s explosive and unpredictable, but also fiercely loyal. Mother and son have a complicated, overly dependent relationship. As Die explains, Steve has an attachment disorder. And she is devoted to him. Steve’s father died a few years earlier and now they are each other’s whole world, living in something of a pressure cooker environment threatening to explode at the first sign of trouble. Some relief and hope arrives in the shape of kindly neighbour Kyla (Suzanne Clément) who has problems of her own. She’s a teacher, on leave for an indefinite period of time and for reasons that remain unexplained. She also has a stutter. Helping with home schooling and becoming a friend to both mother and son Kyla becomes a positive, stabilising force in their lives.

Recounted like this Mommy sounds a little like a soap opera of family dysfunction and motherly love. But of course it’s much more than this.

Dolan creates an immersive landscape of drab interiors and exteriors that teem with contradictory emotions. There is hope and euphoria, despair and violence. But his masterstroke, of which much has already been written since Cannes, is the way he presents this space. He positions his characters in close-up and closed up within the frame by using the 1:1 screen ratio that literally reduces the screen space to a box like form. Dolan uses this squeezed space to show just how compressed Die and Steve’s world is, but also to trap us, the audience, right inside it along with them. Each shot feels like a close up. It’s claustrophobic at times, distressing but ultimately moving. A pivotal scene, in which Steve’s violent tendencies erupt into a full-scale verbal and physical battle with Die, is as powerful as it is because of this reduced screen space. We feel what they feel – the difficulty of escape, the inevitability of conflict. The performances of the leads are all sublime, amplified at times to feel like they might just break the screen wide open. Style is in service to the substance of the story Dolan is telling in the most astonishing way. Trapped in Die and Steve (and Kyla’s) world, I wasn’t just seeing Mommy with my eyes, I was feeling it with every part of my body too.

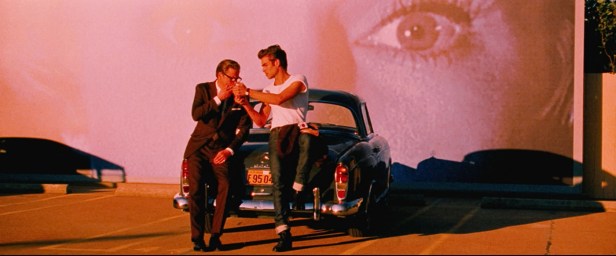

I think Dolan is moving his camera in magnificent new directions because he understands the fundamental truth about cinema – it is an image machine above all else. If you ever need reminding of that, watch a silent film like Chaplin’s City Lights (1931) or the astonishing Le Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) by Carl Theodor Dreyer, or a ‘talkie’ like L’Avventura (1960, Michelangelo Antonioni), Vivre Sa Vie (1962, Jean-Luc Godard), Faces (1968, John Cassavetes), Mauvais Sang (1986, Leos Carax), Happy Together (1997, Wong Kar-wai) or A Single Man (2009, Tom Ford) or any other film you love. What do you remember most from it? It may be a significant conversation between characters, but it’s more likely to be a particular image or sequence, a facial expression, a gesture, something physical, tangible, some extraordinary vision of something previously considered ordinary.

For me, cinema’s true power does not come from dialogue driven scenarios. For me, it’s the framing and presentation of images, the structuring of sequences, in motion, that distinguishes cinema from other visual art forms and from a narrative art form like the novel. All are vehicles for storytelling but none bestows new ways of looking (and in turn of understanding and knowing) with greater frequency and authority than cinema does. In a film, the image comes first. It must be framed in a fashion that furthers the narrative and develops character. But most of all it must draw us, the audience, deeper into its core and into the heart of the film. It has to be there for a reason. Just how it does this is often more difficult to explain with words.

When cinema works at that level, instinctive and responsive, it’s almost like opera. Its impact is measured beyond logic and outside intellect, even if a great intellect has fabricated it. Its primary impact is sensory and physical; working at a sensory and physical level, it’s often able to effect a sincere and surprising change in how we feel. Even the small, quiet moments should swell with dynamic, colossal feelings. Our hearts should beat and burst with it.

From what I can tell, Dolan has been working on achieving this effect since the start of his filmmaking career. He is a filmmaker finely attuned to the physical properties – the viscera – of cinema.

Like Mommy, Heartbeats features an excess of close-ups to extraordinary effect.

Telling the story of Francis (Xavier Dolan) and Marie’s (Monia Chokri) ‘imaginary love’ (as per the film’s original French title which translates as The Imaginary Lovers) for Nicolas (Niels Schneider) a ‘blond Adonis’ they meet at a party, Heartbeats has been accused of being excessively beautiful to look at but not about much more than that. Dolan has noted that the film’s surface is important to him as a way of articulating the shallowness of his trio and about the nature of love imagery itself. It’s the reason why I think a scene in which Francis desperately purchases a packet of squidgy marshmallows (he’s still high after Nicolas has fed him one around the campfire on a recent weekend away and wants to relive the moment) and Dolan cuts to an imagined image of Nicolas, serenely posed against a blue background as marshmallows rain down around him, is able to surpass mawkishness to become something quite magical instead.

I can’t deny the film’s beauty. Firstly, the three leads (Dolan included), as our first point of engagement with the narrative, are lovely. And there are moments of luscious, swoony beauty beyond their physical forms. Dolan uses colour so expressively – a primary palette that is indicative of mood and emotional tone, with red and rose naturally expressive of the flushes of attraction and desire; cooler, washed out blue-grey tones, melancholy detachment. Brushstrokes that remind me of similarly bold evocations by Pedro Almodóvar. Close-ups at unexpected angles invite us to look at things differently. The intimacy of the scene in which Francis confesses ‘Je t’aime’ to Nicolas has all of the raw sensitivity of the scene it’s clearly riffing on between River Phoenix and Keanu Reeves around the campfire from My Own Private Idaho (1991, Gus Van Sant).

Like the cinema’s other great sensualist, Wong Kar-wai, Dolan uses slow motion to intensify feeling and magnify experience. Like Kar-wai, Dolan scores these slow-mo sequences to recurring pop songs; in Heartbeats it’s Dalida’s campy but gorgeous ‘Bang Bang.’ Some critics have accused Heartbeats of being no more than a series of sequences resembling extended music video clips, but I love Dolan’s way with music and it feels to me more like a filmmaker exploring techniques that draw us deeper into the story than its so-called ‘shallow’ surface would permit.

But how we respond to that, again, isn’t so simple to explain. There is a scene in Heartbeats that might be given the music video clip tag, but it’s a scene with such cinematic alchemy that the instinctive response I have to it every single time I watch it (and I’ve rewatched it at least a dozen times now) elevates it to a whole other realm.

It involves dancing, strobe lights, slow motion and the awesome beats of The Knife’s ‘Pass This On.’

Francis and Marie attend a party at Nicolas’ apartment. The party scene is dominated by a high energy, kinetic dance sequence in which Dolan bathes the dancers in a transfixing blue light as their bodies pulse to the aforementioned song. Francis and Marie, bathed in a complementary red light, don’t dance, but sit and watch with lovelorn eyes as a deliriously drunk Nico dances with his mother (Anne Dorval in a fetching bright blue wig) and his other guests.

Dolan cuts between Nico dancing, Francis and Marie watching, and their love projections – Marie imagines him as Michelangelo’s David while Francis sees him as a figure in the drawings from Jean Cocteau’s The White Paper. Colour, music, faces, physical forms. It doesn’t seem like too complicated a formula. But the result is a hypnotic scene that demands a kinaesthetic response. Dolan wants you to feel it with every part of your body. And I did. But it was also so instinctive I could almost feel Francis and Marie’s hearts beating and bursting with desire alongside mine.

The focus on faces in close up creates a deep intimacy, which is ultimately what throbs most persistently beneath the brashness of Dolan’s visual display. And if in Heartbeats slow motion and music intensify this feeling and engagement, there is a similar effect in Mommy when the screen ratio suddenly widens.

Life is improving for Steve and Die. She’s working; he’s learning, with help from Kyla. He’s still full of uncontrolled rages, but is finding ways of channeling them, that don’t lead to violence. His world is opening up.

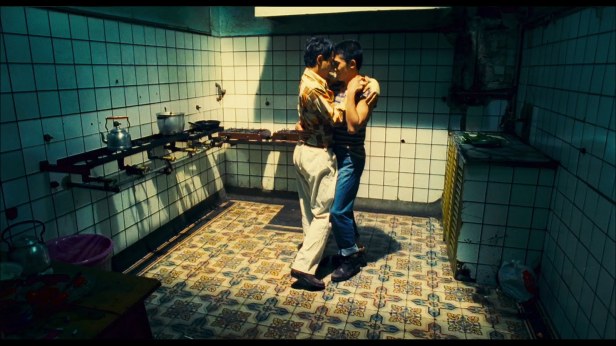

Skating in the middle of the road on his longboard as Die and Kyla trail behind with a shopping trolley, Steve stretches his arms out and opens the screen to its full size. Oasis’ ‘Wonderwall’ moves the scene along. The song is more than just something playing in the background (the songs in the film include Celine Dion’s ‘On Ne Change Pas’ playing in a beautiful scene in which the three characters dance in the kitchen, and other 90s pop songs by Counting Crows and Dido), but something that characters interact directly with. There is absolute sincerity in Dolan’s musical choices and they help to sew together all of our sensory responses to a scene.

This experiment is the complete opposite of showy or cheesy. It’s incredibly alive. Dolan’s technical choice here creates a very specific feeling. It left me in an almost euphoric state. In Dolan’s hands, artifice becomes a completely natural and integral element of the storytelling process. It’s another perfect, sensual moment, so revelatory of character, so deep in service to narrative. Steve’s arms pushing that screen wide open is liberating and thoroughly intoxicating and all the more powerful when events eventually take another turn for the worse and it solemnly contracts back to its restricted form. In many ways, it’s an experience beyond words.

Young people have big feelings. Xavier Dolan is only 25. You can’t read a review or interview with him that doesn’t fanatically point this out or label him the ‘enfant terrible’ of French-Canadian cinema. Yes, he’s only 25, and he’s a talent on the rise, gifted, bold and very exciting. I think he’s invigorating cinema with electricity and daring in part because of his youth. But the fact that he’s only 25 isn’t what excites me most about his films. It’s that he’s only getting started. I love what he’s doing but I also really can’t wait to see what he’s going to do when he’s 35, 45 and beyond.

Heartbeats is the appetizer to the full operatic assault that Mommy is. It’s a film that’s confirmed my belief that cinema, when all notes are in perfect harmony, can move you like no other art form. By the film’s exhilarating final scene, my heart was beating so hard it was ready to burst right out of my chest. Turns out, that’s actually a pretty great feeling.