I have a sizeable crush on a man I see nearly every day of the week. Some days we chat a bit, other days we don’t and I have to be content with watching him from a distance. I guess it’s time to do something about it or turn it off.

I rather inappropriately confess these feelings in my film blog not in pursuit of relationship advice but as a preface to today’s topic. I really shouldn’t be so rubbish at love stuff – I have watched so many films you would think I have a pretty solid script that tells me what to do next. But is it possible that I am watching the wrong films?

With the exception of the genius that is Annie Hall (and any other of the great Woody Allen love comedies, including Manhattan and Hannah and Her Sisters) and the always charming, When Harry Met Sally… (1989), I don’t have a high tolerance for conventional romantic comedy. Of course I understand that they are designed to be light, happy-ever-after fun. And I have nothing against laughing. But when it comes to showing us something about the nature of love, many romantic comedies are just fluff. From Sleepless in Seattle (1993) to How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days (2003) to more recent examples such as He’s Just Not that Into (2009) and Valentine’s Day (2010) and its sister film New Year’s Eve (2011), it’s a genre made up of rather passionless fare, with insipid, bloodless performances, and actors more concerned with looking good than looking in love. Affairs to forget, not remember.

My preference is for romantic dramas (classic and contemporary) and American indie love stories – films that span the spectrum from Casablanca (1942) to (500) Days of Summer (2009). Like the AFI’s 2002 list ‘100 Years … 100 Passions’ (a list of America’s 100 greatest movie love stories) my preference is for films where love is a fever that burns right through the silver screen and desires are so sincere even the audience aches.

Let’s be honest – the nature of romantic love remains a mystery to most of us. Even if we have it in our lives or are in hot pursuit of it, it’s a phenomenon difficult to explain, especially in words. But because it’s a visual medium, I think film can help us to get a little closer (the way poetry does with the spoken word). When we watch love on screen, we don’t just want to see it or hear people philosophising – we want to feel it. If a film can achieve this I think it’s something special.

I recently saw Terence Davies’ beautiful new film, The Deep Blue Sea. It stars the luminous Rachel Weisz as Hester Collyer, the younger wife of Sir William Collyer, a London judge (Simon Russell Beale), who embarks on a passionate affair with a younger, handsome and feckless, World War II RAF veteran, Freddie Page (Tom Hiddleston). Set somewhere ‘around 1950’ the film (based on Terence Ratigan’s 1952 play) takes place mostly in a day – integrating a series of fragmented flashbacks – in the aftermath of Hester’s failed suicide attempt.

Davies’ film has forced me to ask myself a few questions in the context of a life spent watching many films about love. There are a few things I want answers to. What does love look like up on the screen? Can a film actually capture what it feels like to be in love? What it feels like to want love? Or what it feels like to lose love? Does love really mean “never having to say you’re sorry”? What lessons about love have I learnt from the movies?

The main lesson I seem to have learnt is that love hurts.

Love hurts if you have tasted love then lost it. It definitely hurts if you love someone but they don’t know it. Love also hurts if they do know it but circumstances keep you apart.

Some films show us the sheer force of unfulfilled love by measuring how intensely these feelings continue to run throughout a character’s life once the object of affection is out of the picture.

Martin Scorsese’s gorgeous The Age of Innocence (1993) dramatises this better than just about any film I have ever seen. The film’s haunting final scene, where Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis) refuses to visit the woman he should have married, Ellen Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer) – preferring to sit on the Paris street and remember her as she was at the height of his love for her – has broken my heart into smithereens each of the dozen or so times I’ve watched it.

Other films show us that the power of a consummated love can only be measured if we get to see the impact on a character of its loss.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) is a great example of this. This Charlie Kaufman scripted, Michel Gondry directed film, sets up an interesting premise about how far we might go to get over the pain of a lost love by creating a procedure that literally erases them from the brain. When their relationship ends, Clementine (Kate Winslet) visits Lacuna, Inc. to have the procedure done. Angry at discovering this, Joel (Jim Carrey) follows suit, but finds he isn’t willing to give up his memories of her so easily. In the end, the good feelings outlive the bad reminding us that painful memories are only one part of any love story. Losing even these can be devastating. And when Joel and Clementine meet again, the attraction remains, even though their memories of each other are gone. Love, or something like it, survives the procedure, showing us that it is one of the core human compulsions to continuously seek this connection despite the risks and the possible hurt.

I’ve also learnt that really great love stories rarely have happy endings.

This is certainly true of Casablanca and other classics such as Gone with the Wind (1939) and West Side Story (1961). Lovers don’t always end up together. Love often ends in tears. Or separation. And sometimes even death.

The tragedy of lovers separated by time and history illuminates Anthony Minghella’s The English Patient (1996), on a grand scale. Similarly, Joe Wright’s Atonement (2007) separates its lovers, Cecilia (Keira Knightley) and Robbie (James McAvoy) by false accusations and war. But in both films the power of love continues to have force even after death – it endures through memories, through language, and in the lives of other people.

The Deep Blue Sea presents a love that is consummated but on the verge of being lost forever. For my money, this film does what a great love story should – it overwhelms an audience with sheer, unadulterated emotion. This is something that romantic comedies, suffocated by frocks, froth and glamour, don’t even know how to start to do.

Hester’s situation is heartbreaking. She is the embodiment of how far a person is willing to go for love, and how much they are willing to give up. For her, love, is all-consuming. In a flashback, her prickly mother-in-law warns her, ‘Beware of passion … it always leads to something ugly.’ Passion is the key urge around which Hester reorganises her life. It’s what she craves and lacks in her marriage and when she finds it with Freddie she abandons everything for it and will do anything to retain it. Returning to a life without passion, once tasted, is an unbearable prospect and she would rather die than live without it.

This is where we meet her. Something is no longer right between her and Freddie, although we never hear a precise explanation about what has gone wrong.

I found it interesting that for a film based on a play dialogue is the least important cinematic element here. The opening scene, a wonderful sweeping series of shots that take us from the street outside into Hester’s flat and then back and forth through time is almost devoid of dialogue. Davies, like any great storyteller, is showing not telling, concerned with the representation of feeling over thought. Moving fluidly between Hester’s current state – alone, post-suicide attempt in her dreary flat – and the warmth of her memories of falling in love, the intensity of the physical intimacy she experiences with Freddie, immediately establishes the point of view as hers. Hester feels alive when she is with Freddie. We are encouraged to feel as she does, to see her passion as anything but ugly.

Concerned and confused, Sir William asks, ‘What happened to you Hester?’ to which she matter-of-factly replies, ‘Love.’ He is convinced her feelings for Freddie are no more than lust, their connection only sexual. And while part of the problem between Hester and Freddie does seem to be a disparity in their feelings towards each other (he can’t love her as much as she loves him and they both know it), Hester doesn’t care to define it for Bill. She simply says, ‘He is my whole world.’ This is enough; this tells her whole story. When he withdraws his love her world crumbles, in ruins, like the brown, austere postwar London she lives in.

Hester’s emotions are always close to the surface. But a love where the dial’s turned up to eleven at all times can be destructive. What happens in these relationships, fuelled by fire and drama, when that passion dies? As we see in The Deep Blue Sea, hopelessness, barrenness remains. Love, here, is measured by the impact of its loss. It drives Hester to dangerous places where, as she tells her practical landlady, she feels caught ‘between the devil and the deep blue sea.’ She can’t let go even though she knows it’s over.

On the morning when he will finally leave her to go work in Rio, Freddie reveals he is not without feeling, admitting he will miss her, but sure that if they stay together they will tear each other apart. Ultimately, Hester can only go on living without him, and the film’s wonderful final shot pans away from her standing at the window of the flat, out onto the street, placing her amongst other people all caught in their own struggles, absorbing her into the fabric of the wider world.

I’ve also learnt that the experience of love is often defined by regret.

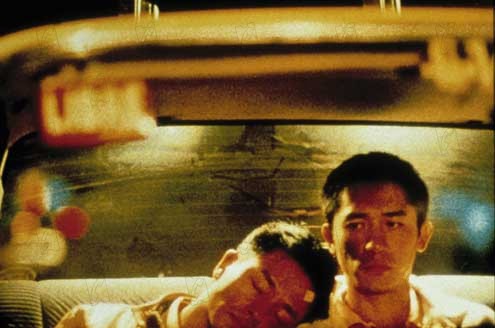

The fragile, sometimes fleeting nature of love, is at the heart of most Wong Kar-wai films, and especially, his two greatest – Happy Together (1997) and In the Mood for Love (2000). Both highly visual films, with exquisite settings and music, show us what it feels like to want love, to find love and to lose it. The performances are convincing – Tony Leung is superb in both films in such different roles – and the worlds they live in sensual and tangible. In the Mood for Love, depicting an unconsummated passion, aches with the pain of things unsaid and acts undone that will haunt these characters’ lives. Happy Together explores the ruins of love with a dysfunctional couple (the late Leslie Cheung plays Leung’s more volatile other half) falling apart while living together in Buenos Aires. Their demise is a slow one, complete with a melancholy tango and moments of intense intimacy and just as intense loneliness. Both are films that convey regret with such poignancy you can’t help feel it right along with these gorgeous, lovelorn characters.

But the flipside of regret is chance. And the movies have taught me to try not to waste it if it comes along.

The delicate space between wasted opportunities and taking chances shapes the brilliant pair of films, Before Sunrise (1995) and Before Sunset (2004), directed by Richard Linklater and starring Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy.

I’m a card-holding member of Generation X, so these films are practically my national anthems. And they explore the questions of what might have been and what could be just about better than any others I know.

In the first film, set over the course of a day and night spent walking around Vienna, Jessie and Celine show us that any magic in the world exists in trying to understand someone else and deciding to share yourself with them. From the moment that Jessie suggests she leave the train with him (‘If I don’t ask you this it’s going to haunt me the rest of my life’) love is a palpable possibility. They walk and talk and slowly reveal more and more of themselves. The scene in the record store listening booth is a perfect little example of what it feels like to fall in love – a little claustrophobic, as your world reduces around one other person. But love also expands your horizons, and we see this as they head back outside, into the city, for more walking and talking.

The attraction between Jessie and Celine is present from the beginning and evolves naturally, as it does when you realise time is of the essence and that ‘everything we do in life is a way to be loved a little more.’ I really like that they don’t play games and there are no spectacular fireworks announcing that now, suddenly, they are in love. They sleep together in a park (we only have this confirmed in the second film) and farewell each other at the station the following morning promising to meet in six months time because neither can bear the idea of never seeing each other again. You want it to happen. All this in a film where no one says ‘I love you,’ yet you have no doubt that they do.

Before Sunset picks up nine years later in Paris, where Jessie has come for the last stop of his book tour. He’s now married with a four-year-old son but has never forgotten that brief time he spent with Celine. His first novel, This Time, is about her – he wrote it to try and find her. It works – she shows up at the book signing at Shakespeare & Co and they spend the day walking around the city until he has to catch his flight home. As he tells her, ‘I remember that night better than I do entire years.’

The question looms large – did they meet that December in Vienna as they had promised. At a café, Celine explains that she wanted to be there more than anything but that her grandmother died and they buried her on that day. Initially joking that he didn’t go, Jessie eventually admits that he was there, furious with himself for not exchanging phone numbers or surnames. Later, Jessie confesses to being unhappy in his marriage and that he thought about her on his wedding day. He wonders, often, what would have happened if they had met up, how ‘our lives might have been so much different.’ Now, Celine is cynical and Jessie wonders if he didn’t completely lose faith in romantic love when he was left standing at the station in Vienna alone.

But they have another chance, another opportunity to connect. The film ends at Celine’s apartment, after she sings him a waltz about a one-night stand she wrote about their time together. It’s pretty clear Jessie will miss his flight. I’m desperate for the next instalment.

At the risk of sounding like a broken down record, I’ll say it again – you just don’t get these lessons in love from romantic comedy.

But there is one exception to the rule for me – an unconventional romantic comedy that had me lovesick when I first saw it. It’s as good a time as any to revisit it here now.

The aches and pains of love pulse all the way through Steven Shainberg’s darkly comic Secretary (2003). It’s a film that makes me laugh but also makes me feel something more. I couldn’t help a wicked giggle at the quirky courtship between Mr Grey – an obsessive-compulsive lawyer played by James Spader – and his masochistic, self-mutilating secretary, Lee (the wonderful Maggie Gyllenhaal).

After one too many typos, Mr Grey spanks Lee, and a few typos later, they’re in love. But what appears to be a twisted tale of S&M power play in the workplace is, quite unexpectedly, a tender, ecstatic experience – possibly one of the most passionate love stories in recent memory. Two people who think they are unlovable get together in the most unexpected way.

Strange as it seems, Secretary is a love story in the old-school style. Like Paul Thomas Anderson’s equally heady and eccentric fable, Punch-Drunk Love (2002), here romance is a thing of sweats and fevers, where obsessive needs outweigh logic. Despite its bondage scenarios, Secretary avoids being merely salacious because Lee is utterly consumed by the pursuit of love. She suffers blissfully at Mr Grey’s sadistic hand because he makes her feel alive. It’s no wonder that her fervent desire also seduces an emotion-starved audience.

When you think Secretary has no surprises left, it pulls out a bona fide sweet Hollywood ending – with a fluffy wedding dress, a steamy bathroom scene and a burning realisation that without each other, Lee and Mr Grey can’t go on. Just as in the classics, you can’t help but feel their pain. When it hurts this much, you know it’s good.

You can take a look at the full AFI list ‘100 Years … 100 Passions’ here: http://www.afi.com/100years/passions.aspx

The Age of Innocence is indeed, beautiful & heartbreaking, it has such a haunting quality to it. Daniel Day-Lewis and Michelle Pfeiffer are as emotionally compelling any couple I can remember.

Thanks for reading Paul. I appreciate it. The Age of Innocence remains one of my most beloved films. I remember the initial discussion about it when it came out as being so unlike anything Scorsese had ever made before, despite his usual attention to detail and extraordinary camerawork also on show here. But the film also contains a brutality comparable to his other films, even if here the violence is delivered with whispered gossip rather than fists.

Thanks for the welcome. I read on another of your posts that you saw The Age of Innocence on the first day of its release, and the day after finishing the book. That must have been an incredible experience.

The Age of Innocence is a film that is almost never screened in film revivals, when its quality demands that it should be shown regularly. The detail Scorsese lavishes on the film’s art direction and the exquisite costume design make it one of the most visually ravishing films ever made.

Absolutely. I have it on good authority that it will be screening as part of a Scorsese program here in Melbourne later this year and I’m really looking forward to the experience of seeing it on a big screen again. Seeing it the way I did the first time was pretty amazing.

I wish I could be there.