“The art of screen acting has two chapters – ‘Before Brando’ and ‘After Brando’.”

You might call it much ado about a little cotton, but since he’s wearing it in nearly every scene of the film, you’ll excuse me for writing an entire post about it. And anyway, just take a look at him in it – it’s the kind of image that crawls into your psyche and simply refuses to leave.

The first time I saw Marlon Brando in that t-shirt, I was seventeen years old. I was in my final year of high school, in my favourite class (English Literature) with the best teacher I’ve ever had. We were studying A Streetcar Named Desire and once we were done with the print text, the teacher suggested we watch a film version. He brought in the 1984 made for television adaptation starring Treat Williams as Stanley Kowalski and Ann-Margret as Blanche DuBois. It was OK, but once we were done with that I had a quiet word with my teacher and suggested we contrast that with the classic 1951 adaptation, directed by Elia Kazan and starring Brando as Stanley, Vivien Leigh as Blanche and Kim Hunter as her sister and Stanley’s wife, Stella. He agreed and I brought in a VHS copy we had at home.

I wonder now, as an adult, whether my teacher knew something I didn’t when he initially chose the other version of the film for the class – that perhaps the sight of Marlon Brando in that t-shirt might be too much for his mostly female teenage cohort to handle. Williams was a perfectly adequate Stanley, but possessed none of Brando’s raw, exhilarating blend of sexual allure and danger. How could he? Stanley Kowalski is one of Brando’s most iconic roles (he originated it on Broadway under Kazan as director in 1947) – it’s a performance rarely matched, never bettered.

I still remember watching the Kazan film for the first time. I don’t know if I fully understood the play at that point – had really grasped that Stanley rapes Blanche and triggers the full mental breakdown that sees her dramatically exit the play. What I seemed to take away from Streetcar in my youthful naïveté was the flipping in my tummy whenever Brando as the brutish Stanley was on screen.

I’d had plenty of cinema crushes throughout my teens – River Phoenix, Andrew McCarthy, Johnny Depp. Good actors (actually, River was great) but all pretty boys. Brando was different. When Stella points him out to Blanche at the bowling alley she comments, “Isn’t he wonderful looking?” I couldn’t help but agree.

Marlon Brando at 27 years of age was beautiful, wonderfully masculine and extremely sexy. His lips, sensual and full, almost womanly. His dark eyes, big and warm and deep. His body, at this time, pretty close to perfect. As many have noted, Brando in his prime had the face of a poet and the body of a prizefighter. From what I could see, Brando was a man. With or without the t-shirt he was an actor you simply couldn’t take your eyes off; an actor who dominated any space he was in. As Kazan said of him, “It’s like he’s carrying his own spotlight.”

When is a t-shirt not a t-shirt? In A Streetcar Named Desire the cotton t-shirt fitted to Brando’s body seems like a second skin. It’s an integral aspect of Brando’s characterisation – the external skin that helped him to get inside Stanley’s skin. Sometimes the t-shirt is clean and freshly pressed. In other scenes, it is stained and sweaty, sticking to Brando in all the right places.

Until Streetcar, t-shirts were really only worn as an undergarment or by wrestlers. They were originally developed as a slip-on garment to be worn under uniforms during the Spanish Civil War. Marines then continued wearing them while stationed in warmer climates. Other tales suggest that the US Navy adopted the white common undershirt in 1913, to be worn under overalls to conceal sailors’ chest hair. Farmers during the Depression wore t-shirts as a lighter and cheaper alternative to the button up shirt.

Brando’s t-shirts were made especially for him, as a fitted t-shirt didn’t exist at the time of the film’s production. The costume team had to wash it several times to shrink it and then sewed it tight in the back.

Brando as Stanley Kowalski made the t-shirt something more than an undergarment. By the time James Dean donned a t-shirt in Rebel Without A Cause (1955, Nicholas Ray) it would become the uniform of teenagers all across America and Europe along with blue jeans and a leather jacket – part of a dress code that stood for rebellion against old values. Wearing a t-shirt sent out a social message.

But as it appeared in Streetcar with Brando’s beautiful physique poured into it, the t-shirt also sent out a message about masculinity explicitly tied up with new methods of acting. It might be a stretch, but I also see it as emblematic of his approach to acting – how Brando wears his characters like a second skin.

When Brando first appears in the film, he enters his New Orleans house after a session at the bowling alley. It’s also his first meeting with his sister-in-law Blanche. Completely unselfconscious, he removes his jacket to reveal a t-shirt stuck to his wet chest. He asks Blanche, “Hey, you mind if I make myself comfortable. My shirt’s sticking to me.” He disrobes and stands shirtless in front of Blanche who is visibly unnerved by the sight of his body. And then he pulls on another shirt. Later, after they have sized each other up a bit, Blanche expresses her approval of his character: “Simple, straight-forward and honest … a little bit on the primitive side.”

When the 19-year-old Brando arrived in New York in the late spring of 1943 he began taking acting classes and eventually ended up being mentored by Stella Adler. Adler had spent the 1930s working with the Group Theatre – the experimental company founded by Harold Clurman, Cheryl Crawford and Lee Strasberg. The Group Theatre – and later, the Actor’s Studio – were leading interpreters of Stanislavski’s ‘Method’ in the United States. This was an approach to acting that would revolutionise American theatre, and in turn, American screen acting in the 1950s.

At the heart of the Method is a shift away from classical acting techniques and a move towards more lifelike performances. Method actors create character from the inside out – focusing on emotions, senses, and the psychology of their character to present the action of a script. Actors are encouraged to identify personally with the character they are portraying, recalling their own experiences, responses, and memories to reproduce the character’s emotional life. As Brando explained, with this approach, the actor doesn’t so much become someone else as he becomes himself.

Adler, after studying directly under Stanislavski took this approach further, distancing herself from the Method taught by Strasberg. Adler eventually promoted the idea that actors not use their personal memories, but rather the circumstances and context of any given scene to create emotion. Adler believed that drawing on personal emotion was too limiting and encouraged her students to use their imaginations to fully explore the possibilities of their characters. One of her mottoes was, “Don’t act. Behave.”

The Method changed American screen acting for good, and for the better. What we got to see in films after Brando was acting that basically didn’t look like acting – performances so raw and so fully embodied that they truly seem real.

From what I can see, this acting style – see Brando, Dean and Clift, and later Pacino and De Niro – is defined by its physicality. Emotional expression isn’t limited to exaggerated facial movements or rises and falls in voice – it comes from the subtlest shifts in eyes, drops in shoulders (see Dean all through East of Eden), and other movements. It takes in props (see Brando taking Eva Marie Saint’s glove from her and putting it on his own hand in a totally improvised and brilliant scene from On the Waterfront) and interacts with the natural environment presented by the set. The Method also gave us a new American manhood – softer, more expressive, and unafraid to feel, unafraid to open its heart and bleed on screen for us.

In Streetcar can anything surpass the ‘Stella’ staircase scene in which Stanley appears, his t-shirt ripped from their earlier argument, his skin exposed and pieces of wet cotton falling to reveal more and more of him? Stanley slinks outside to the bottom of the staircase, crying out for the woman he loves. It’s so sensual and tangible that you can’t help forget what has brought him to this point – that he’s been drunk and argumentative and abusive. Brando is more provocative and exposed in that soaked t-shirt than most contemporary actors manage to be when they are nearly naked.

For me, that scene is the summit of what Brando does throughout all of Streetcar – he’s pure flesh, carnal, instinctive and vulnerable. He burns alive on the screen in ways his co-stars – who it has to be said, are all exceptional – can only dream of being. Brando’s reputation for mumbling throughout his career only further serves to explain the significance of his physical presence on screen. Brando is Stanley, and while he’s on the record saying that Stanley was everything he detested in men, he so fully embodies him that you can’t see where actor and character begin and end. This performance is enough, in my opinion, to anoint him the greatest screen actor of all time.

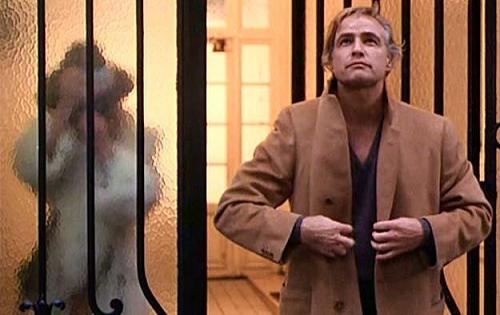

I want to say a few more things about t-shirts and second skins so I can write about what is arguably Brando’s last great performance – after his Oscar-winning role in The Godfather (1972, Francis Ford Coppola) – as Paul in Last Tango in Paris (1972, Bernardo Bertolucci). I’m not going to talk about passing the butter or whether this film is bad for women. I love this film and I love it because it gives me Brando being everything I want Brando to be.

In his late forties when he shot Last Tango in Paris, Brando was no longer the beautiful young man of his twenties (a persona he felt trapped by). Although softer around the belly, he remained an imposing figure, still completely dominating the screen, older but always handsome.

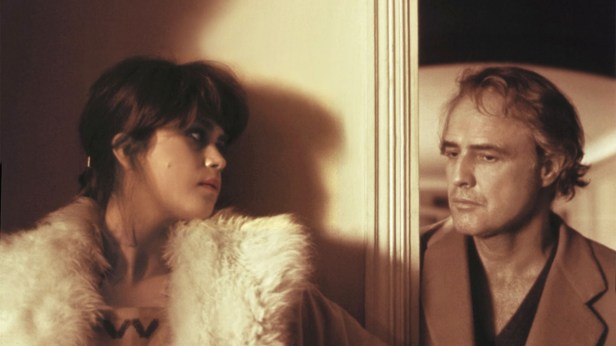

In Tango he is Paul, an expatriate American living in Paris, who we encounter in the immediate wake of his wife’s suicide screaming for “Fucking God” under a bridge as a train roars past. The film can be seen as an exploration of his attempt to sort out the turmoil of his grief through a series of anonymous sexual encounters and intimate conversations in a flat with a young woman called Jeanne (Maria Schneider). With her, Paul tries to erase himself and then put himself back together again.

Throughout Bertolucci’s film, Brando’s astonishing abilities are on show in all their wild, ferocious glory. It is a physical film – sex, dancing – and Brando overwhelms the screen, but once again much of his action is focused inward. As the great American film critic, Pauline Kael wrote in her famous New Yorker review, he is “intuitive, rapt, princely.” She concluded that, “On the screen Brando is our genius”.

Brando wears Stanley’s t-shirt in the Paris flat – although it’s not such a tight fit anymore, you make the connection with this t-shirt from one performance of masculinity to another. In both films, but especially Tango, Brando’s method draws us in close and we struggle along with him.

What’s discomfiting for me as a viewer about Last Tango in Paris, isn’t the often cruel nature of the sex, but the feeling I have watching this film that I’m not watching a performance by Brando so much as an act of self-revelation. Many of the film’s scenes were improvised, under Bertolucci’s direction, effectively drawing Brando’s real life into Paul’s fictional one. The sequence in which Paul talks to his dead wife’s lover, Marcel (Massimo Girotti) is a charming and clever example of this. Brando looks at Girotti’s face and comments that he must have been handsome twenty years ago (he was), to which Girotti responds, ‘Not as much as you.’

Like his great roles from the 1950s, here Brando is all instinct, imbuing every action – spilling champagne on Schneider in the wonderful ballroom scene, kicking his shoes off, edging the butter closer with his foot, the slow, detail of his actions when he bathes her, grunting and groaning in place of words – with some internal truth. There is sadness, eroticism, passion, immaturity, playfulness, aggression, tenderness and despair. He is self-destructive but seeking redemption. It’s a full spectrum of human emotion. Everything is stripped back, extending way beyond realism into some other realm; it’s honestly quite difficult to put its impact into words because so much of it is visceral, dependent on visual codes, and also specific to the time and space that Brando occupies within each scene as Paul. Really, you just have to see it.

In a 1974 feminist critique of the film entitled ‘Importance and ultimate failure of Last Tango in Paris’, published in Jump Cut, E. Ann Kaplan suggests that ‘the sheer strength of Brando’s personality in a film like this is jarring.’ Kaplan wants audiences to be able to take a position about Paul – to either fully like or dislike him – and proposes that it is unsuitable for us to feel close to a character who is brutal and insensitive. She argues, ‘as Brando’s acting style draws us close to the character, it only leaves us puzzled as to what he is really all about, or what we are to feel towards him.’

But for me, feeling ambivalent about a character is an okay position to be in as a viewer. As it is in reality so it is in the cinema – it’s okay to accept that a person or character contains multitudes of often contradictory selves. And very few actors are able to convey this truth successfully.

Kael suggested that Last Tango in Paris was both the most powerfully erotic and most liberating film ever made. She may be right, even today. I’d add to this that Brando’s performance in this film is his freest and most searching. It lets you forgive some of his earlier (and later) indiscretions. Here, Brando shatters his own image (which he was in constant conflict with), daring us to reject and even hate him. But some of us only end up loving him even more. There are no accents, no concealing prosthetics or make-up. There’s just Brando wearing his character like a tight t-shirt, like a second skin: tender, brutal, unadulterated, extraordinary.

You can read Pauline Kael’s rapturous review of Last Tango in Paris here in full: http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/834-last-tango-in-paris

I seriously have to agree with everything in this article. I love the last tango in Paris because it shows a different side of Brando that he wasn’t able to explore in the 50s.

Thanks. The shifts culturally in the 1970s, and the fact that it’s a European art film, certainly allowed him to open up in different ways as an actor. I would have liked to see him do more like that, but apparently he found the experience very emotionally exhausting. Thanks for reading.