How Oscar Isaac shows us what’s not on the page

There’s a scene in the Coen Brothers’ new film, Inside Llewyn Davis, which demands a closer look.

It takes place past the halfway mark. Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaac) is in Chicago, at the famed Gate of Horn nightclub, where he has taken himself to audition for folk impresario Bud Grossman (F. Murray Abraham) modeled on the real life Albert Grossman, who opened the club in 1956.

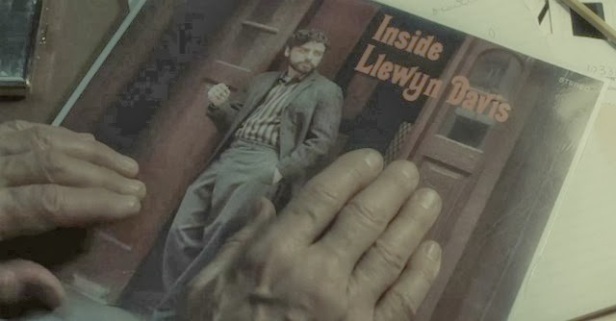

Llewyn arrives wanting to know if Grossman has had a chance to listen to his debut solo album, Inside Llewyn Davis, and he says no, but he’ll hear him sing something now from the album. Llewyn sings ‘The Death of Queen Jane,’ a deeply melancholy traditional English ballad about the death of Queen Jane (Seymour) after giving birth. The song provides an affecting look inside Llewyn Davis and how he is feeling at this point in the narrative. What Grossman doesn’t know is that Llewyn has just organized an abortion for his some time lover and fellow singer Jean (Carey Mulligan) who is married to Jim (Justin Timberlake) but could be pregnant with his child, and has also received some unexpected news about an ex-girlfriend who was pregnant with his child a few years earlier.

Grossman wants to hear something from inside Llewyn Davis

Grossman wants to hear something from inside Llewyn DavisIt’s a really beautiful moment in the film, especially when Llewyn puts down his guitar and sings the final, moving stanza unaccompanied. But Grossman is unmoved. He ‘can’t see any money’ and thinks Llewyn should be part of a group, not a front man, because he’s not able to ‘connect.’ But from what we, the audience, have just witnessed, we know this to be untrue. When Llewyn explains that he had a partner (more on this below), Grossman suggests he gets back together with him. Llewyn doesn’t explain that this is impossible and simply agrees that it would be a good idea and leaves.

The Coens stage the scene simply, with minimal lighting and it is clear how exposed Llewyn is at this moment (and Isaac in turn) and how cavernous his disappointment is when Grossman blankly rejects his music, what he’s feeling and him.

This is just one of many scenes in which Oscar Isaac pushes us a little closer to answering the question of just what it is that’s inside Llewyn Davis.

Inside Llewyn Davis begins where it will end, with a few significant differences that I won’t spoil for you here. It’s 1961, Greenwich Village, and Llewyn is a folk singer, struggling to make ends meet, taking advantage of the exhausted generosity of friends and their couches and his well-meaning sister and generally slumping his way through his life. He is also an evangelist for the old tradition of folk songs and their ability to transcend time, as he says, ‘If it was never new, and it never gets old, then it’s a folk song.’ But the times they are a-changing and he’s not catching up. He openly loathes and mocks the hits new singers are producing, and we are encouraged to laugh along with him at their square sweaters and sweet melodies as much as we are encouraged to find him snobbish and difficult.

The film begins, evocatively, with a close up on a microphone and then a close up on Llewyn singing ‘Hang Me, Oh Hang Me.’ The performance is notable for its intimacy, and I think the Coens want us, at this point, to be on Llewyn’s side. Whether we stay there throughout the film is another thing. After his set, he’s summoned outside into the alley behind the Gaslight Café, where we see him brutally beaten by a mysterious stranger who suggests the beating is retribution for some heckling Llewyn has dished up to another performer at some other time. We will have to wait for nearly the entire film to uncover and understand what he did to deserve this.

Llewyn Davis sings in the film’s opening scene

Llewyn Davis sings in the film’s opening sceneLlewyn continues to get beaten, emotionally and spiritually, throughout the film. But he’s already pretty bruised by life and its disappointments, some of his own making, others beyond his control. He holds onto his desire to live an authentic life with increasing desperation. As Jean describes him, everything he touches turns to shit, he’s like ‘King Midas’ idiot brother.’

The Coens don’t give us a lot of Llewyn’s back-story yet I think Isaac delivers a character that’s fully formed, with a life before and after the limits of the screenplay and film world. Great acting does that. It’s for this reason, I think, that while Llewyn often behaves in unlikable ways and repeatedly thwarts his chances at happiness (whether being a ‘likable’ protagonist is even important is a topic for a whole other post) we still care about him. I cared about him a lot. And I think I cared because Isaac gives us a sense of a much bigger story, even if we are only getting a small part of it here. Isaac’s performance is notable for its subtlety, for how it carefully traverses the tragic and comic elements of his character. He’s a wildly charismatic actor and his is a performance that goes beyond the scripted page.

Oscar Isaac is the real deal

Oscar Isaac is the real dealWriting about the film recently in The New Republic David Thomson says he’s bothered by the word ‘inside’ because this is a terrain that the Coens don’t traverse; they don’t do ‘emotional profundity.’

I disagree with this assessment of the Coen brothers work. And I especially disagree in relation to Inside Llewyn Davis. I’ve been reading a lot of commentary on this film in the past week since I watched it, and it’s interesting how quick writers have been to label Llewyn an ‘asshole’ and the film ‘soulless.’ There may well be something wrong with me or maybe I was watching a different film to everyone else but I don’t feel this way about either Llewyn or the atmospheric story the Coens have crafted.

As the film unfolds, in its lyrical, circular fashion, we learn that Llewyn’s musical partner, Mike (the voice that we hear on the soundtrack belongs to Marcus Mumford) has recently died after throwing himself from the George Washington Bridge. It is a death, I think, that hangs over Llewyn’s entire story. Little is expressed, in words, of the significance of this loss or the sadness that now characterizes much of Llewyn’s life. He doesn’t talk about it with anyone but reacts with rage at dinner with his Upper West Side intellectual friends, Mitch and Lillian Gorfein (Ethan Phillips and Robin Bartlett) when Lillian innocently attempts to sing Mike’s part in ‘Fare Thee Well.’ In a different film, Llewyn might follow this explosion by extrapolating at length about how he is feeling, cry and be comforted by friends and family, but this is not that kind of film.

Yet, it’s pretty clear that the loss is a profound one for Llewyn, mixed with sadness, despair, and perhaps guilt, as suicides often are. This complexity of feeling, this emotional profundity is all there in the silent moments of Isaac’s performance. Isaac delivers a layered and restrained performance full of melancholy. As Tim Grierson writes in Paste on the occasion of Isaac’s ‘snubbing’ by the Academy, ‘Beautifully reserved yet hinting at his characters unknowable depths of sadness and frustration, Isaac gives Inside Llewyn Davis its spirit, its humor, its beautiful poignancy.’

On another friend’s couch, Llewyn contemplates life

On another friend’s couch, Llewyn contemplates lifeAnd if it’s a reserved performance it’s a performance that explodes with life during the musical numbers (all filmed live). I found it impossible not to support Llewyn, to empathise with his sense of outrage about the folk music scene, to wish him success despite his frustrating behavior and multiple acts of self-sabotage.

The irony of this is not lost on me, that while Llewyn Davis is a failure (of sorts), Isaac’s nuanced performance is a real success.

What did Isaac do to draw me in, to make me care, to make me want the best for his Llewyn?

This has all got me thinking – what exactly is good acting and how do we know it when we see it?

I doubt I can unravel this mystery, but I’m going to have a try.

In a recent article for the Slate Book Review, Phillip Maciak raised this very question. He says, and I agree, that ‘Film acting is the last great mystery of the contemporary cinema.’ While those of us who talk and think about cinema regularly feel quite adept at analyzing the processes involved in directing or special effects, the language we have to talk about how acting happens is more diffuse, much more difficult.

Maciak elaborates:

‘The film actor … creates a role through “presence,” “gravitas,” or simply the application of a mysterious, and innate, “it” factor. Celebrity actors may have human foibles, but they also possess an indescribable aura that is constitutive of their power over us. Even Stanislavski’s infamous “method” approach is suffused with the language of “magic” and “illusion.” We know that there are processes involved in the creation of a screen performance, but, more often than not, even the process stories we tell about actors are about a kind of prestidigitation—Daniel Day-Lewis becomes possessed by Abraham Lincoln or Charlize Theron disappears within the grotesque visage of a serial killer. We know how acting works, but there is a horizon beyond which the craft remains opaque, even mystical.’

But is great acting really magic? Does great acting only happen when an actor disappears so far into a character that they are no longer visible to the audience? Or is great acting about something much less showy?

I’ve just taken a quick look back over all the things I’ve written about since this blog began and the one constant in my writing, the thing that has compelled me most often to sit down and tap at the keys of my MacBook Pro, is my connection to a film’s characters, characters who ultimately exist only because an actor has breathed life into them.

Regular readers will know I’ve spent a lot of time writing about actors and thinking about the particulars of their appeal. Some of you may think that I’m a little star-struck or too easily swayed by a handsome face. But that’s not it at all. My focus is most often on the actor and their performance because I think that’s the most powerful and reliable way to test a film’s emotional barometer.

So I’ll get this out of the way now, before I move on. I’ll confess that I have, for a long time, thought that Oscar Isaac is handsome, in that slightly goofy way I find most appealing. He’s very nice to look at. But he’s also really interesting to watch. In all the films I’ve seen him in he hasn’t overplayed his scenes; he always seems to hit just the right chord. There is a confidence and sexiness to him, to be sure, but also a soulfulness and warmth that are immediately appealing, qualities that don’t seem affected but rather whisper for our attention. That’s the stuff underneath, the stuff that doesn’t feel like acting.

In Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive (2011), for example, as Carey Mulligan’s recently paroled husband, Standard Gabriel, he brought serious depth to what was finally a minor role. He seemed to understand what drove this broken man, and in turn we felt for him in unexpected ways. As Maggie Gyllenhaal once said in an interview, what she loves about being an actor is that it allows you to practice compassion for others. And the best actors do seem to me to do this, to really express the experience of being another person with honesty and truth.

There are some actors you connect with and some you don’t and I don’t think there is much you can do about that. I’m going to call this the empathy riddle. As I mentioned to a friend recently, as much as I liked Gravity (2012, Alfonso Cuarón), I couldn’t love it because I failed to connect to Sandra Bullock’s character (or maybe, she failed to connect with me). But I’m not surprised because I have never really connected with any character she has played. I haven’t ever felt able to delve beneath her surface. In any of her performances, I haven’t ever felt what’s not on the page.

Sandra Bullock in Gravity – an actress I struggle to connect with

Sandra Bullock in Gravity – an actress I struggle to connect withI’ve never done it, but I think acting must be hard work. I suspect, however, that the best make it look effortless.

Meryl Streep is an interesting case study on this point. Almost universally lauded as the greatest living actress and praised, uncritically, for almost everything she does, Streep, when you look at her filmography closely, has actually had a career of highs and lows.

It started off well with roles in The Deer Hunter (1978), Kramer vs. Kramer (1979), and Sophie’s Choice (1982) – roles that were emotionally charged but generally reigned in much of the flamboyant, broad affectations that make later work in films like She-Devil (1989), Postcards from the Edge (1990), Death Becomes Her (1992), The House of the Spirits (1993), Mamma Mia! (2008) and even Julie & Julia (2009) less digestible. While I watch Streep with as much awe as everyone else that she can do almost anything (and Streep must be lauded for her versatility and for sustaining such a strong career well into her 60s, an age bracket where Hollywood seems happy to dispose of most of its women), I have always preferred her work when it plays against my expectations of her, as it does in Adaptation (2002) and Doubt (2008). While her strength with accents is undeniable (see Out of Africa, The Bridges of Madison County, Evil Angels, Angels in America and The Iron Lady) these are often roles that are impossible to ignore for all the wrong reasons (a similar argument has been hurled at her now Oscar nominated performance in August: Osage County).

Streep in Sophie’s Choice, one of her finest moments

Streep in Sophie’s Choice, one of her finest moments And in She-Devil, one of her worst

And in She-Devil, one of her worstBut what happens when you strip Streep of wigs, accents and prosthetics? Her work in The Hours (2002, Stephen Daldry), I think, is one of the films that show Streep at her best. Here, as Clarissa Vaughan, she is pared back to the kernel of her talent. When she breaks down in the kitchen, about halfway through the film, it’s almost a master class in acting. It seems like a real woman, breaking down, and drowning in the quagmire of emotion she’s wading through at that moment. You feel the pain that has come before and you get a sense of an inner life without it all being described. It’s never overdone and doesn’t scream for attention. Streep’s acting here makes me feel more strongly than ever that the best acting doesn’t look like acting at all. And yet I realise that my explanation here is diffuse, vague, maybe a little ‘touchy-feely’, but it brings me back to my belief that good acting is just something you know when you see it, or maybe more accurately, feel it.

Streep breaks down in the kitchen in The Hours and shows us all how it’s done

Streep breaks down in the kitchen in The Hours and shows us all how it’s doneI felt this same process at work in Inside Llewyn Davis in the aforementioned scenes at the Gate of Horn and at dinner with the Gorfeins. It’s perhaps most intensely visible in the expression on Llewyn’s face when he abandons the ginger tabby – originally the Gorfeins cat, Ulysses, which he loses but then a version of which keeps finding its way back into his life – in the car on the cold road to Chicago. While it’s easy to conclude that Llewyn is incapable of being responsible to anything and anyone, Isaac, wordlessly, also makes us feel the weight of this decision, and that perhaps, after the loss of Mike, it’s too difficult for him to feel attached to anything. The ambiguity of this act and of Llewyn’s feelings about it (and Mike’s death) works in the film’s favour. Isaac’s acting here is sublime and sincere – as it is later when he visits his father in the nursing home and sings ‘The Shoals of Herring’ to him and earlier when he meets with the doctor who will perform Jean’s abortion. There are many moments like this, where Llewyn’s feelings are unvoiced, in dialogue, but we hear them nonetheless.

Llewyn and the cat who circles him throughout most of the film

Llewyn and the cat who circles him throughout most of the filmThe Coens are consummate filmmakers and they have created a character whose so much more than the sum of his actions within the film. He’s not just a loser and an asshole. As Oscar Isaac plays him, he’s a man grappling with grief, depression, loneliness, regret, despair and sadness. He may not say it (he does tell Jean he’s ‘tired’ when he tells her he’s getting out of folk singing) but it’s heavy in his mournful eyes. It’s in his voice when he has words to sing. And it’s somewhere between silence and song, I think, where the film’s warm, gooey centre spills out, and we see what’s really inside Llewyn Davis.

Reblogged this on doubleplusgood. and commented:

These guys a Gods to me… Human flaws never seem quite as bad when the Co Bros are making comment

Gods to me too. Nothing wrong with flaws anyway – we all have them. Thanks or reading and reblogging.

i´m agree, is a very good blog, always recommend it … thanks for sharing!

Thanks for reading.

Really nice point about how the best portrayals show us a character who is fully formed, who pre-existed the film and will continue living after the end of the film. As for what makes unforgettable acting, for me as a viewer I find that the best moments, the moments when I feel the most connection with a character, is when the actor is “doing nothing” or as little as possible. That draws the viewer in and allows the viewer to project themselves into the situation and feel what they would feel if they were in it. Make sense? Anyway, nice post!

Absolutely makes sense. I think that’s part of what I was trying to say – that it’s the silences, the subtle moments, that are the most profound. It’s definitely more difficult to feel connected to a character who never gives you a moment to catch your breath. Thanks so much for reading and for taking the time to comment.

Reblogged this on PUNKNDISORDERLY.

congrats on being FP’d

Thanks Julie. Quite exciting!

Reblogged this on Marcus.Banks and commented:

Great post about acting! (And the movie Inside Llewyn Davis!)

Thanks! Really glad you like it.

Great post, I enjoyed every word of it! I actually think a lot about what makes actors great. When they “disappear” and we see only the characters they play? Or when they possess a certain star quality and we enjoy their cinematic personas (which do not change much depending on the movie)? And should it matter, if we, as you named it, connect with their characters? For a long time my favorite actor was Daniel Day-Lewis because he completely disappears. However, I started to appreciate the so-called “character actors” more and more. They cannot disappear as easily, yet their performances are often brilliant.

Thanks so much. Daniel Day-Lewis is also one of my favourite actors, and I was thinking of going into some detail about his method alongside my discussion of Meryl Streep, but didn’t want the post to get out of control. What I find interesting about him, as an actor who does disappear completely into a character (and you don’t necessarily get a sense of the man behind the mask) is that there is still something quite subtle (at least for me) about his process and the result. He never feels like he’s hamming it up, if you know what I mean, and I think that maybe that’s the point at which his ‘greatness’ diverges with someone like Meryl Streep’s ‘greatness’ because she often does. Whether he plays an historical figure like Lincoln or a fictional character like Daniel Plainview (in There Will Be Blood) I don’t watch and think ‘oh, look that’s Daniel Day-Lewis’, I actually tend to forget I’m watching him. By comparison, I watch Streep in The Iron Lady and I can still see her behind the mask, and for that reason her performance in that film feels more like an impersonation.

enjoyed reading this keep up the good work

Thanks and thanks.

Reblogged this on changeforus59.

Looks like a cool film. I should go and see it! Thank you for informing me about it.

This is a great article! I really enjoyed your writing style and your obvious connection with the character, very insightful.

I absolutely adore the Coen Brothers, talented minds, very talented indeed.

Cheers!

Thanks Kevin.

I haven’t seen this movie, but reading this is like the perfect primer for doing so. I think everybody should read this before they see the movie to get the most out of it!

That’s very kind of you to say. Go and see it!

I almost read this earlier today, but stopped myself. A few hours later and I’m back from watching Inside Llewyn Davis and… well every thought I had you’ve articulated perfectly above. Great article!

Thanks so much – it’s just my opinion, but I’m always glad to find other people who feel the same way.

Reblogged this on http://www.worldbestentertainment.com.

Thanks Larry.

I loved this movie and your review is spot on. Congratulations on being Freshly Pressed!

Thanks!

Reblogged this on NeilKeene Blogsite and commented:

Must see in Oscar season.

I so enjoyed reading this! I too got all of that depth and feeling out of the film despite what so many people have said about it. I think Isaac’s acting is incredible and profound in this film. Those eyes, and those silences, really moved me. Well done for putting it so well 🙂

Cool, thanks for reading. It’s all about casting isn’t it? Some roles just feel made for certain actors and this is one of those where everything feels right.

Reblogged this on Thekynegro29's Blog.

Reblogged this on Sweetened-Condensed.

Reblogged this on Travels and commented:

Loved “Inside Llewyn Davis.” Was lost without words when I tried to write a review. Thankfully I found one. Have a look!

nice article!

http://www.dryguywaterproofing.com

Nicely written.

Thanks so much for the comment and for reading.

I take you’re a Joy Division fan?

Yes, I am. But also of the noir film In a Lonely Place starring Bogart.

Excellent article. There are so many levels to Inside Llewyn Davis. I certainly think its a film that can be watched over and over again to reveal its hidden depths. Possibly the best Cohen movie so far.

Thanks. I am really looking forward to revisiting it soon. I have a few other films to catch up with first, but then I want to spend some more time with Llewyn.

I’m with you on basically every point you’ve made ranging from Oscar Isaac’s incredibly soulful acting performance to the lack of connection you felt with Sandra Bullock’s character in Gravity. Poins well taken about Streep too.

Thanks for your comment – I never write expecting anyone to agree with what I think, but I’m always pleased when someone does.

Another excellent movie review about the most underrated American movie of 2013. I wrote a review about Inside as well with a theory regarding the meanings of the two cats in the film. Would love to know what you think

http://observationblogger.wordpress.com/2014/02/08/the-best-film-no-one-will-talk-about-this-awards-season-inside-llewyn-davis/