In my thirty-something years I’ve only ever shed tears over two ‘celebrity’ deaths: River Phoenix and Jeff Buckley.

River was the first. It was 1993. I’d just turned nineteen and my first year of university was coming to a close. When the news came through from the US my mum woke me to tell me. My first response was to roll over and cry – I’m not ashamed to say – an uncontrollable, river of tears.

I’ve often wondered what triggered that response.

There were more tears when Jeff Buckley drowned in the Mississippi River on May 29, 1997. That hit me hard. After he went missing, I remember days and days of walking around campus, listening to the radio and waiting for his body to be recovered. I was trying to read Freud and Faulkner with knots in the pit of my gut sure it was going to be bad news.

A week later, when his body surfaced, I had to work at the campus bookstore and try to keep it together. It wasn’t easy – I just wanted to hide beneath my doona with ‘Lover, You Should Have Come Over’ on repeat.

Thinking about my behaviour now, the excesses of my response to events I was technically removed from, maybe I should laugh or attribute it to youth or my predilection towards doomed romanticism, but I don’t. As ridiculous as it sounds, his loss felt personal.

I think the bonds we forge with performing artists – be they musicians or actors – despite never really knowing them, can be formidable. I don’t know if other people feel this way, but it’s always been this intense for me. They become a part of your life, your emotional makeup, and sometimes in quite profound ways.

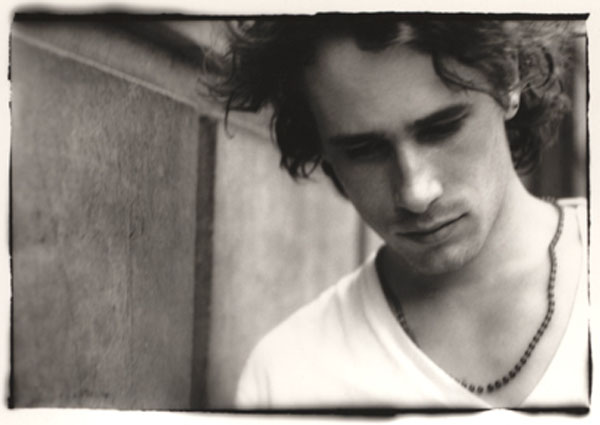

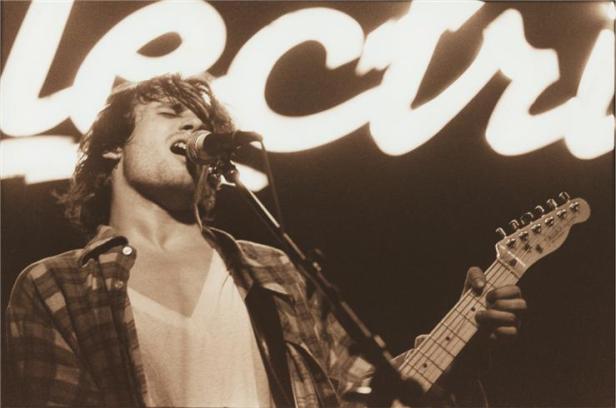

I often tell people that I think I was one of the first people in Australia to ever hear Jeff Buckley sing, very late one Sunday night on the radio, just before Grace was released in 1994. Jeff Buckley was my little secret and being a Scorpio (like Jeff was) I knew how to keep him close, sharing him only with a select few.

I had the privilege to see him perform live twice – when he first toured here in Melbourne in September 1995 and again the year after. When I queued on a rainy Friday morning for tickets to the first tour with a small group of converts, I felt like my status was cemented. Lots of people I’ve spoken to in the years since wish they’d attended those intimate pub gigs at the tail-end of his first world tour. Music fans will often talk about transcendent experiences, about the connection and communion of live music as a quasi-religious experience (like the cinema), and Buckley’s performance in a tiny, grungy inner-city pub where I could practically reach out and touch him, was exactly that. It’s a cliché to say it, but in that room of 200 other disciples, it felt like Jeff Buckley was singing only for me.

(Although it’s completely off topic, I feel the need to correct those of you who buy into the whole Buckley had a ‘voice like an angel’ thing, by sharing that my experience of him live was of an altogether sexier, earthbound creature. If pushed, I prefer Rolling Stone’s description of him having ‘a voice like an oversexed angel.’)

My memory of that night is perfected by a personal memento. I had the audacity (albeit nervously) to ask Jeff for his autograph as he stood shyly beside the bar before the gig. I was struck by how small and fragile he was and despite me feeling like I was getting in his way he just smiled that gorgeous toothy grin of his and happily signed my copy of Grace with the following words: ‘Jo, Mad love, Jeff Buckley.’

While I’m not an advocate of stalking or hysterical fandom (I’m thinking of screaming Bieber fans here), I do think that it’s the ultimate goal of creative people to connect with others, to transcend time and space via whatever it is they create. I’d like to think that it’s a tribute to these artists that their loss doesn’t go unnoticed. You passionately experience their art and if you continue to care for it when they’re gone you feel protective of it, like you’re guarding a legacy on their behalf. And for me personally, when I love something – a film, a song, or a book – I love it hard.

I connected with Jeff because of the intimacy of his performances – he seemed to strip back another layer of skin, cut out another little piece of his heart, every time he opened his mouth.

River Phoenix’s best performances are also distinctive for their intimacy, for his bruised toughness and his effortless ability to make you care immensely for him from the moment he appears on screen. As a teenager I instinctively felt protective of his misunderstood Chris Chambers in Stand by Me (1986) and of his conflicted Danny Pope in Running on Empty (1988), his Oscar nominated role. And his finest performance (his breakaway from the teen idol status that vexed him), in My Own Private Idaho (1991, Gus Van Sant), is often difficult to watch for this reason – its abundant intimacy makes me care so much it hurts.

Phoenix, just nineteen going on twenty when Idaho was made, exposed something quite special on screen under Gus Van Sant’s direction. It’s one of the most understated and sensitive expressions of a character I’ve seen in any film. But then he was gone. Dead at 23 from heart failure, after a series of violent seizures, most likely caused by a speedball, collapsing on the dirty pavement outside the Viper Room, while his younger sister Rain and brother Joaquin desperately tried to revive him.

So losing River was personal for me too. Only I didn’t realise how much until now.

My Own Private Idaho is a testament to River Phoenix’s beauty, vulnerability and most importantly his abundant, multifaceted acting talent, which was both intense and mischievous (he won the Volpi Cup for Best Actor at Venice in 1992, Best Male Lead at the Independent Spirit Awards and Best Actor from the National Society of Film Critics). I hadn’t watched it for a long time. When I watched then re-watched it the other night I remembered exactly how I felt the first time I saw it.

And as a film lover, I remembered what we lost when we lost him. There was the possibility of countless other sublime performances to come as he was moving from ‘teen actor’ to leading man in interesting indie films (he is also edgy and excellent in Peter Bogdanovich’s The Thing Called Love released in 1993). Two weeks after his death Phoenix was due to start work on Neil Jordan’s Interview with the Vampire. His role went to Christian Slater. He was also being pursued for the leads in The Basketball Diaries and Total Eclipse which both eventually went to Leonardo DiCaprio.

But as Ryan Gilbey, writing in The Guardian on the tenth anniversary of River’s death noted, he is ‘the forgotten man of late-20th-century film acting.’ And for me this is an upsetting fact. Gilbey asks a good question: ‘Do the young fans of Leonardo DiCaprio, Tobey Maguire and Jake Gyllenhaal even know that there was an actor in the recent past who would make their idols look like bantamweights?’ From a brief survey of Gen Y-ers in my workplace I’d say, probably not. Sadly, most of them have never even heard of River Phoenix.

(Recent news that River’s last movie – Dark Blood, directed by George Sluizer – incomplete at the time of his death, has been finished and will premiere at the Netherlands Film Festival in September has been welcomed by fans all around the world. I have mixed feelings about it but you can watch the trailer here http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M9UIlO3NRng)

In My Own Private Idaho, Phoenix plays Mike Waters, a young hustler living on the streets of Portland. It’s a sort of road movie, although there is little actual movement along America’s roads. Despite this, throughout the course of the film Mike will travel from Idaho to Seattle to Portland to Idaho to Rome to Portland and then back to Idaho again. Idaho’s where he comes from and he’s going back in search of some lost part of himself. Ultimately, the film doesn’t go anywhere but this is part of its beauty. It just opens the possibility of movement, as Mike says at the end of the film, ‘This road will never end … it probably goes all around the world.’ He’s not necessarily talking about a real road, but maybe the road in his mind, where the potential is endless.

My Own Private Idaho has multiple personalities and is almost a different film depending on which of its many locations it’s in. (Van Sant’s main source materials for the finished Idaho screenplay were two separate scripts and a short story, all written by him.) But the film’s heart is its journey to Idaho. These scenes have a beautiful strangeness to them, a dreamlike autumnal hue foreign to most glossy American films. And it’s all anchored by Phoenix’s intense melancholy, his enigmatic quality. There’s a distinct emotional palette to the Idaho scenes too that later colours the Italian scenes when Mike is left alone and heartbroken.

The film opens with Mike standing on the side of a two-lane highway. It’s Idaho. It’s a scene that will be repeated at the film’s end. It’s a vast, lonely landscape, deserted and empty. The camera shows us the road and then Phoenix enters from the left and fills the screen, blinking as if seeing light for the first time. He touches his face, his fingernails dirty, in an almost self-conscious way. But he’s beautiful and scruffy and from this moment on you won’t take your eyes off him. He has no one to interact with so he interacts with a landscape that mirrors the landscape of his own soul. He connects with us through raw physical expression – the actors’ most potent tools.

We hear his thoughts: ‘I always know where I am by the way the road looks … Like I just know that I’ve been here before, I just know I’ve been stuck here.’

In this opening scene, which features numerous, almost disorienting close-ups on Phoenix’s face, we engage with his vulnerability as an actor and we immediately care about his character. We wonder why he’s on the road and we wonder how he got there. He has a duffle bag but he doesn’t seem to know where to go. And then suddenly his hand starts shaking and he collapses and falls to the ground.

Mike is narcoleptic. It makes living a ‘normal’ life, which he craves, a bit of a challenge. He’s an outsider among outsiders. Moments of stress (and they are numerous) cause him to go to sleep. He regularly depends upon the kindness of strangers to make sure no harm comes to him.

One of those strangers is actually his best friend, Scott Favor (played by Phoenix’s real life best friend Keanu Reeves). Where Mike is poor, Scott is rich. He’s the son of the Mayor of Portland, born into privilege, but slumming it on the streets as a hustler, having sex with men for money partly as a ‘fuck you’ to his dad and partly to satisfy his ego, not because he has to do it to survive.

The narcolepsy gives Mike and his journey a sort of dreamy detachment and this is the quality that Van Sant paints his film with. The theme of drifting through life without an anchor is a strong one.

The film’s title is drawn from the B-52’s pop song ‘Private Idaho.’ To live ‘inside an Idaho potato’ means to live in a small space, to be confined to a narrow sphere because of daydreams or distractions. Narcolepsy means Mike’s always living with an altered sense of time.

Time stands still quite a bit throughout My Own Private Idaho. It’s a film filled to bursting with intimate, private moments. My favourite remains Mike’s campfire confession, a scene that comes at around the middle of the narrative.

After some time in Portland, Scott agrees to help Mike find his mother, who troubles his dreams with surreal visions, like home movies stuck on play in his mind. When they arrive in Idaho, Scott’s motorbike gives up, so they build a fire in a nearby field and settle in for the night.

Mike’s secretly in love with Scott and having the chance to talk he wants to know what he means to him, confessing, awkwardly, ‘I’d like to talk with you … I don’t feel like I can be close to you.’ He knows they’re friends but he says this because he wants to be closer. Scott uneasily asks, ‘How close?’ and Mike asks, ‘What do I mean to you?’ But when Scott says they’re best friends (trying to delay what’s coming), Mike pulls back, ‘That’s okay. We’re gonna be friends.’ Scott declares that ‘two guys can’t love each other’ and he reminds Mike that he only has sex with them for money.

Mike feels very differently. He may have sex to survive but what he really wants is love: ‘I could love someone even if … you know, I wasn’t paid for it. I love you … and you don’t pay me.’ Phoenix crouches closer to the fire at this point. This is a major revelation, as if Mike’s just discovered this truth about himself and is letting us discover it with him.

The camera stays with Phoenix, when hopefully and desperately, laying it all on the line, he says, ‘I really want to kiss you, man.’

Mike doesn’t get the response he’s looking for so says ‘Good night now’ lowers his head but then looks up again and says ‘I love you though.’ And again, revealing more, ‘You know that, I do love you.’ These feelings are real and Phoenix plays it with complete conviction and emotional truth as he turns inwards, in a seated fetal position. He’s exposed and vulnerable and Scott has no choice but to respond to it, to show him some kindness.

Scott calls him over and holds him saying, ‘Let’s just go to sleep.’ The scene ends and we don’t know what their embrace becomes. Van Sant gives us no clues in the scenes that follow the next day. All we know is that Mike still loves Scott and that his heart breaks in two when he abandons him in Rome. Mike’s journey is marked by this catastrophe – a confession of love that leads to ruin, that leads to loss, that leads to the exact opposite of what it should have.

This is one of my favourite scenes in any film I’ve ever seen and Phoenix is sweet and absolutely magnetic. He’s fully clothed but naked. His awkwardness is natural, unstudied. He speaks softly, fumbling to express himself, like you do when you’re unsure how the object of your desire will respond to your declaration. As they are throughout most of the film Phoenix’s shoulders curve forward, his eyes look down (Phoenix had a slightly lazy right eye that always gave him a slightly apprehensive expression), but he still burns right through the screen. His emotional authenticity comes from his introspection. I’m not sure there has been an actor since him with the same kind of grace. It’s only a short scene but watching what he does in it, I want it to go on forever.

The scene is all the more extraordinary when you learn that Phoenix actually wrote it, expanding it from a mere two pages in the script to eight. Van Sant considered Mike asexual, that sex was just something he traded in, but Phoenix decided early on that Mike wasn’t just hitting on Scott cause he was horny and bored but because he’s gay and in love with him and he built his character, and this scene, around this truth.

My Own Private Idaho is considered a landmark film for the New Queer Cinema (a term coined by B. Ruby Rich in a 1992 Village Voice article to describe a renaissance in gay and lesbian filmmaking in America) and this scene contributes to that status, I think because we see a gay man baring his heart and soul. (There’s also no denying that Phoenix and Reeves make a really gorgeous couple, but I digress.)

But it’s also a landmark for showing the ways in which men crave connections of a different kind. The emotional intimacy of the campfire scene is repeated when Mike visits his older brother Richard (James Russo) in his run-down trailer. We get closer to Mike in these scenes and learn that as a baby he was put in an institution because the state deemed it unsafe for him to live with his mother. Later, Mike calls his brother ‘Dad,’ and while there’s no proper explanation – Richard tries to tell Mike the truth about their mother, but in his desperation to belong to someone, he won’t hear it – it’s suggested that he’s both his brother and father.

Watching both these scenes (campfire and trailer) I feel like an intruder, invading a private space, listening in on very personal conversations. In the trailer scene, Van Sant’s camera encourages our trespass into a moment of private despair, sitting as it does just above River’s forehead as he breaks down.

But it’s these scenes that give River Phoenix the chance to shine. Phoenix wears the role of Mike like a flayed second skin. He’s emotionally expressive and physically dynamic. Like James Dean he acts with every part of his body; like Dean he vanishes so deep into a character you almost forget you are watching a film (comparisons between the two extend well beyond the fact that they both died young in tragic circumstances before their full potential was explored). My Own Private Idaho might be Generation X’s East of Eden. Like Dean, Phoenix knew how to make the audience fall in love with him. From beginning to end, River draws me in and holds me close; he makes me care, makes me want to reach in and hug him, makes me want to protect him all over again.

(Off topic again, but it’s worth noting that 1991 was also the year of Nirvana’s Nevermind where another young man with a gentle bruised quality opened up some deep, private part of himself and shared it with us. I felt a similar desire to hug and protect Kurt.)

In an interview, Phoenix said this about his craft: ‘It’s about caring and empathizing and wanting to create the best, the most true to life, the most real.’ And there is something truly empathetic about him – he expressed this quality and he extracted it from his audience. And while the young Leonardo DiCaprio had some of this energy, as did the late Heath Ledger, neither quite has his glow. And I’m like a moth to the flame for it.

Van Sant’s style (later perfected in Gerry, Elephant, Last Days, Milk and Paranoid Park) is fluid and hypnotic. He’s not a filmmaker interested in loud moments. His camera takes its time to explore something deeper than action. If the New Queer Cinema is a cinema that explores difference, this isn’t restricted to subject matter, but can also be applied to our understanding of cinematic style. My Own Private Idaho is a delicate film and it uses images in strange, poetic ways. If you don’t believe me, turn off the sound and just watch.

My Own Private Idaho ends right back where it started – on that lonely Idaho highway we first find Mike on. As he tells us, he’s a connoisseur of roads, ‘I’ve been tasting roads my whole life.’ Mike falls asleep again and you are reminded of how vulnerable he really is when two strangers pull up in a truck, steal his shoes and his bag and drive away. Not long after, another car pulls up, picks Mike up and drives off with him. We don’t know who he is or what he intends, but as the credits roll I need to believe that it’s an act of kindness and not something else. (I’ve always wanted it to be Scott, but on the Criterion Collection DVD extras a conversation between Van Sant and Todd Haynes reveals that it’s supposed to be Richard, Mike’s brother/father. If you watch carefully you’ll see that the car you catch a glimpse of out front of Richard’s trailer does resemble the car that picks Mike up at the end.)

The lives of male street hustlers in Portland couldn’t be further from my own experience of life but the film’s emotional core couldn’t be closer. With the campfire confession as its burning heart, Mike’s story is a story we can all relate to – male or female, gay or straight – a story of unrequited love and loss. My Own Private Idaho is a film about the desire we all have to belong somewhere, to something and to someone. We all want it; we just go about getting it in different ways. Sometimes we win and sometimes we don’t.

The title of this post is mine. He is my own private River. But he is also James Franco’s.

Just before his Oscar hosting gig in 2011, Hollywood’s own Renaissance man premiered an installation of video art at Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills – a two-film exhibit entitled ‘Unfinished’. It comprised of Endless Idaho (12 hours of discarded dailies from the My Own Private Idaho shoot) and My Own Private River, 102 minutes cut from these dailies into a film that places Phoenix’s Mike at the centre of all scenes. My Own Private River features a score by R.E.M’s Michael Stipe, a very close friend of Phoenix (R.E.M’s 1994 album Monster was dedicated to him). It’s both a tribute to the actor and a close study of his performance. From all reports it’s quite beautiful.

But why remix material that was already cut into a pretty amazing film 20 years ago? Writing a blog post for The Paris Review (‘Mystic River’ September 22, 2011), Franco explained his motivation:

‘Think of all the takes of all the shots of all the movies ever made. Think of all the scenes and angles and alternate readings and alternate lines that were recorded on film – and then discarded in the cutting room. There are endless reels that have been perused and discarded by editors, never to be seen again. Many filmmakers would consider the discarded material worthless, but I … consider all of it valuable.’

Franco is restoring what was lost, and in his own way, bringing River back to life.

Franco has said that My Own Private Idaho is ‘a film that had moved me, that had helped shape me as a teenager.’ His chance to sit down with Van Sant and consider what the film would look like if he were making it today – sparer in story and dialogue, with longer takes and fewer cuts – influenced his creation of My Own Private River. It sounds like a respectful revisioning. I’m sure it wasn’t easy. Franco writes that the discarded material of some actors is inevitably inferior to what makes the final cut of a film, but in the case of River Phoenix ‘every scrap is gold.’

There are no plans to release My Own Private River on DVD in the near future and I haven’t seen more than a small clip from it on The Huffington Post. But I have found some of Van Sant’s dailies on YouTube and they present a captivating study of how an actor slowly builds a character. Among these are a series of extended takes, in close-up, of Mike’s reaction to Scott leaving him alone in Rome to return to America with his new love, Carmella.

In Van Sant’s finished film a devastated Mike runs outside and watches the car drive away down an empty road. Van Sant then cuts to Scott and Carmella in the taxi. We only see Mike from behind which increases his position as an isolated figure, and the next time we see him he is back in the centre of Rome, hustling to return to Portland.

But in this extra material, Mike turns and faces the camera. And for several minutes we simply watch that face. Watch the best actor of his generation doing what he did best. Phoenix captures and holds our gaze even when he says nothing, maybe especially then, with all his natural instincts on display. It’s like watching Chaplin in a silent movie – he creates a character, touch by touch, one nuance layered onto another. He tells us everything we need to know about Mike with those eyes and they tell us his heart is broken. It’s difficult to watch knowing what happened next in Phoenix’s life – it’s really moving and overwhelming – but pure magic all the same. (You can watch this sequence here. River turns and faces the camera at around the 2:50 mark: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wDy2xVsDSj0)

Clearly, Franco has great professional respect for Phoenix, but there is also something more personal at work here. Franco was fifteen when Phoenix died and he’s remained a devoted fan because of the bond he forged with his art at a time when he was starting to figure himself out. After working with Van Sant on the excellent Milk (2009), Franco admitted:

‘I would watch [My Own Private Idaho] a lot, even before I was acting. For some reason it struck a chord with me. I know it’s an incredibly important film for queer cinema, but I wasn’t a young teenager waiting to come out. I guess the emotions it touches on made me want to watch it over and over.’

I wasn’t a young teenager waiting to come out either but I understand what Franco means. Those emotions touched me too. They still do.

Postscript: I was going to wait awhile to post this piece, but since today, August 23, 2012, would have been River’s 42nd birthday, it seemed like the right time to remember him.

Great post, as usual. As it happens, I just showed my Year 12 students a twenty minute clip from My Own Private Idaho last week. We’re studying Henry IV, Part 1, so I showed them the robbery scene/trick on Fat Bob, which is based on the play. Although I believe Van Sant was actually inspired by Orson Welles’ Chimes at Midnight adaptation rather than Shakespeare directly. The composition of Scott’s monologue with Fat Bob behind him directly mimics Welles’ film with Hal’s monologue delivered with Falstaff behind him (it’s actually supposed to be a soliloquy in the play). The students weren’t terribly impressed with it as an adaptation of Shakespeare, unfortunately, and River plays a minor role in the scenes we watched, so I’m afraid they didn’t come away with an appreciation of him as an actor.

Thanks Blair, I think I’m getting the hang of this blogging thing. It is a shame your students didn’t get to see much of River, but one can live in hope they might discover him one day on their own. I find the Fat Bob/Shakespeare scenes interesting, but often feel like they are part of a completely different film and since my focus here was on River, I didn’t delve into that aspect of the story at all. That would be material for a whole other post!

You sure can write Jo.

Thanks Phil. So can you, for that matter. I’ve just read your latest piece over at Chime. Very impressive.

Great post, I’ve love read it.

Thank you. I loved writing it.

One of my biggest inspirations, he was a tour de force and in my honest opinion was similar to Montgomery Clift in the way they poured there soul into there roles, the way they displayed vulnerability and sensitivity so effortlessly. Without a shadow of a doubt a great loss. Hopefully Dark Blood gets wide release so everyone can see his final performance.

Wonderful post. He was my own private River as well. I too was 19 when he passed away and my best friend committed suicide one year before River died. My best friend and I watched this film together and had a special bond to it like most people of our generation. Great piece, and keep on shining!

Cheers. Thanks for that. I think River belongs to our generation. You keep shining too.

” I’ve only ever shed tears over two ‘celebrity’ deaths: River Phoenix and Jeff Buckley. ” – the exactly same feeling I have for River and Jeff !! They are only “celebrities” whom I can not believe they are not alive and feeling saddens !! Thanks !

Thanks for reading 🙂

Being that it is now 2015, I have just turned 40. I am not ashamed to say that the emotions you feel towards these two iconic characters is shared. I also had the privilege of seeing mr Buckley perform in Melbourne. Unfortunatly, they were over the door limit to the pub so despite my pleading ‘I am just one girl’ repeatedly out of desperation I was rejected entry. However I did make it to his next gig. This amazing small man with a fierce passion and cyclonic voice was my word at the time. I also held him close and did not share his music. He’s was mine. I still have my ticket stub to remind me it was real.

I also cried for both of these men, the ideals and characters of both were meant to be shared with the world. And it is a lonely place without them. As a result I now tell those iconic magnificent almost enthreal talents how much they are adored ! Needed and loved even. I have hugged both beck and james mercer,and thanked them, my latetest loves and now make sure my 3.5 year old daughter knows what it means to have the right people imprint on her. Thank you for remembering them!

Thank you for reading and for your comments. I also have those ticket stubs, faded but still glorious reminders of two brilliant nights.