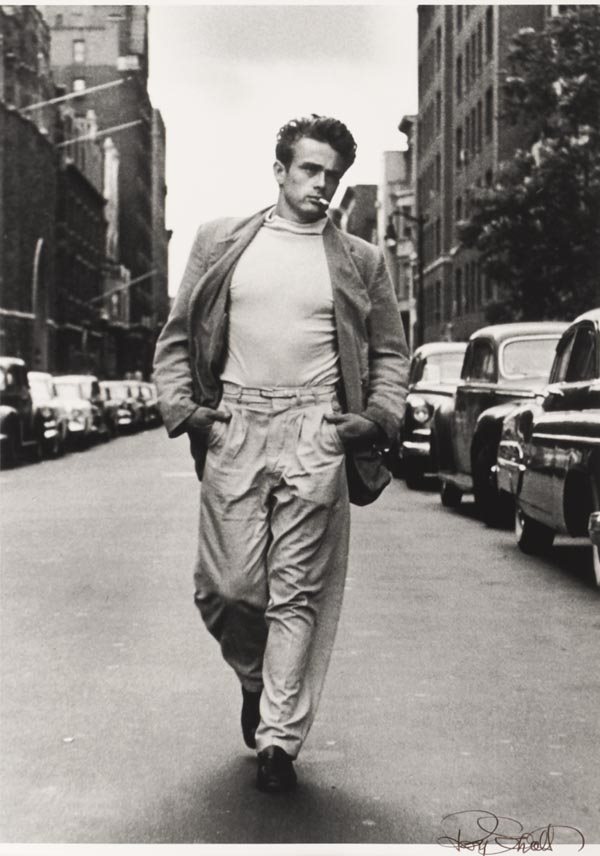

Here is a photo.

People recognise it all around the world. You’ve probably seen it before.

It’s the epitome of cool and the epitome of kitsch – so celebrated maybe it’s become meaningless.

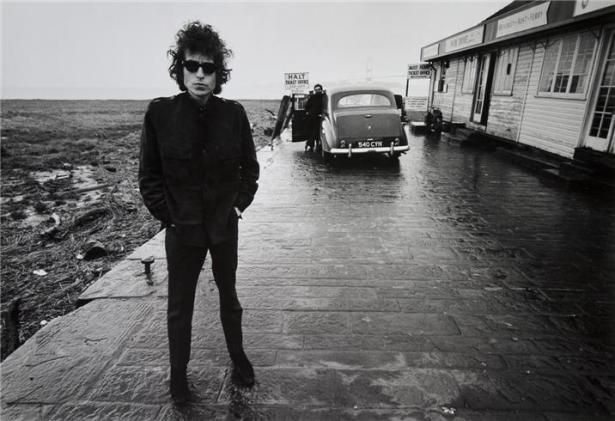

Dennis Stock, a 26-year-old photojournalist with the Magnum Agency, took this photo, ‘On Times Square’ in 1955. The man in the coat, walking in the rain, is James Byron Dean (1931-1955).

Stock met James Dean in Hollywood in January 1955. He was on assignment with Life magazine and followed Dean on a visit to his boyhood home of Fairmount, Indiana, then onto New York where he had made his home – where ‘On Times Square’ was shot in February as Dean made his way to class at the Actor’s Studio – then back to Hollywood, where he took further photos. Stock’s aim was to capture a young movie star in both his professional and personal life. By September of that year, James Dean would be dead.

‘On Times Square’ is a beautiful photo – atmospheric and perfectly composed. But this image, of one of the most significant figures in twentieth century American film has been reduced to something of a cliché by the life it has taken on since Dean’s death. Through endless reproductions and a few parodies, the photo tells a particular story about James Dean the loner, outsider, rebel, not James Dean the actor.

Or does it?

There he is – shoulders hunched, introspective, cigarette dangling from his lips, his body reflected before him as he drifts down the rain-soaked street and into the collective unconscious, into our shared cultural imagination. He’s just one young man in a big city, but he’s one man too important to ignore.

I’ve been looking at this photo a lot lately.

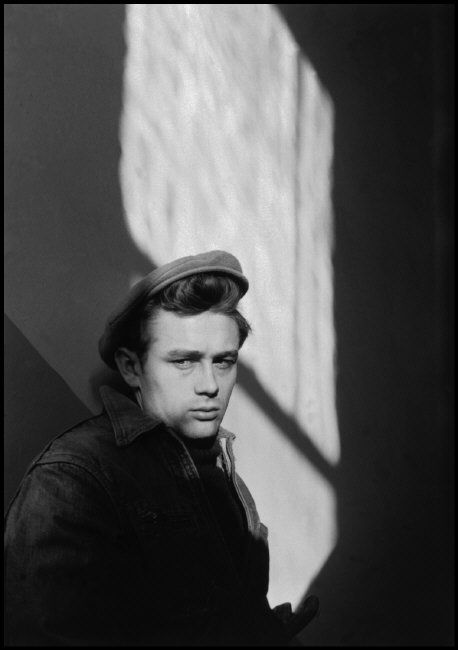

I’ve been looking at a lot of photos of James Dean. He’s easy to look at.

And I recently took another look at his three films – East of Eden (1955, Elia Kazan), Rebel Without a Cause (1955, Nicholas Ray), and Giant (1956, George Stevens).

He has such a beautiful face but actually I can’t take my eyes off his shoulders.

I think everything that makes James Dean an exceptional actor can be found in those shoulders – poised for movement, often hunched, tensed in defence or yielding in surrender. Dean’s posture reveals the internal stress of his characters – Cal Trask, Jim Stark and Jett Rink. He looks beaten down, but he’s loose, not tight, restless and relaxed at the same time. His shoulders wait, on the verge of something explosive. Just like in Stock’s photo.

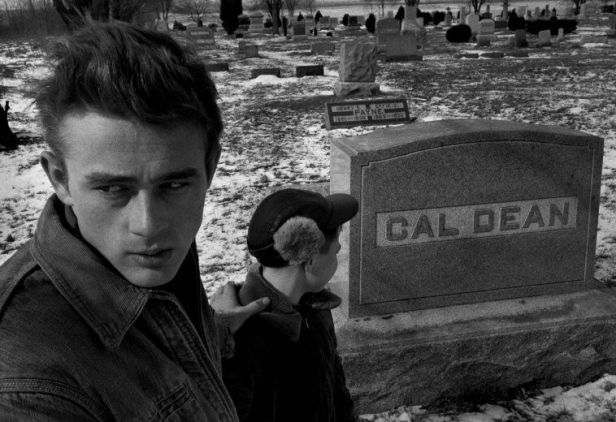

I discovered James Dean when I was in high school. The boy I loved back then looked a lot like him and one of my idols, Morrissey, worshipped him too. The video for Morrissey’s first solo single in 1988, ‘Suedehead,’ was basically a film of Moz, in a heavy coat and Dean-style tortoiseshell frames, walking the streets of Fairmount in the dead of winter, visiting his school and eventually Park Cemetary where he’s buried. It’s a great song and a nice visual pilgrimage. It made me want to know more. (A photo of a young James Dean on a motorcycle also adorns the cover of The Smiths single ‘Bigmouth Strikes Again.’ Before The Smiths, Morrissey wrote a book called James Dean is Not Dead, eventually published in 1983.)

In my final year of high school, ‘On Times Square’ was brought to life as part of McDonald’s ‘MacTime Rocks On’ television commercial (Australia only, I think). It featured a James Dean lookalike walking through Times Square to the sounds of David Essex’s 1973 song, ‘Rock On’, (‘Still looking for that blue jean, baby queen/ Prettiest girl I ever seen/ See her shake on the movie screen, Jimmy Dean’) eating a burger (in place of a cigarette), with a hunched posture that ended in a shot directly referencing Stock’s photo.

The slouch, the hunch, the searching posture, the rounded softness of James Dean’s shoulders suggests many things – awkwardness, longing, submission, nerviness, neediness, vulnerability. On screen Dean was rarely still – his eyes darting, limbs loose and threatening to collapse under him. There is something frenetic about all his performances, always expressive, even when perfectly still.

The movement of James Dean’s body, most distinct through the posture of his shoulders, is in direct contrast with the typical masculine pose worn by leading men of the previous generation, such as Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, Humphrey Bogart and John Wayne. These actors expressed themselves very differently. They stood with shoulders strong and square, their chests held up and pushed out, legs balanced and spread. Their bodies dominated space, expressing their control over their surrounds, rather than suggesting any conflict with it. In contrast, Dean is soft and open – his dropped shoulders an invitation to be vulnerable and the very embodiment of a new way of being male.

Those expressive shoulders are a key element of Dean’s intuitive performance in East of Eden directed by Elia Kazan. Of Dean’s physicality, Kazan has said this:

I felt that Dean’s body was very graphic; it was almost writhing in pain sometimes. He was very twisted, almost like a cripple … He couldn’t do anything straight. He even walked like a crab, as if he were cringing all the time. I felt that, and that doesn’t come across in close-up. Dean was a cripple, anyway, inside – he was not like Brando. People compared them, but there was no similarity. He was a far, far sicker kid, and Brando’s not sick, he’s just troubled. But I also think there was a value in Dean’s face. His face is so desolate and lonely and strange. (Kazan on Directing, 2009, pp185-6)

Dean was an acting novice and as such had little in the way of technique. He was all instinct. It was a natural talent that sprang from his body and not his mind. You don’t catch him thinking on screen. He’s in the moment, just feeling and responding. As Kazan said, ‘he had no proper training. He could not play a part outside his range. He often hit a scene immediately and instinctively right.’ (Kazan on Directing, 2009, p186).

The posture is also part of the physicality that marks the Method acting style, where the communication of emotion takes its cues from a more expressive and open masculinity. In this, James Dean, Montgomery Clift and Marlon Brando are the holy trinity.

Kazan had wanted to make a film with Montgomery Clift and had offered him the part of Cal Trask, despite his being thirty-three at the time, when Brando had turned it down. Clift wouldn’t give Kazan an answer so the director gave the part to the largely unknown twenty-two year old Dean, who had small parts in television movies and some Broadway experience.

After East of Eden, Dean was compared to Clift, which annoyed Monty, who felt that Dean had no range. Clift’s performance in A Place in the Sun mesmerized Dean. But Dean hero-worshipped Brando and would often try telephoning him for advice. Brando said, ‘Dean used to call me … I’d listen to him talking into my answering machine, asking for me, leaving messages, but I never spoke up.’ The only advice Brando ever gave Dean at a party where he was following him around and mimicking him was ‘Be yourself!’ and to give him the name of his analyst.

Patricia Bosworth suggests that Dean modelled himself on Brando – the slouch, the jeans, the loaded silences and sullen expressions. But Kazan has said,

When Brando came to visit my set … Jimmy was awestruck and nearly shrivelled with respect. But I cannot concur in an impression that has some currency, that he fell into Marlon’s mannerisms; he had his own and they were ample. (Kazan on Directing, 2009, pp186-7).

Some critics have suggested that the emergence of James Dean damaged Clift’s career. Clift was constantly being compared to Brando, and vice-versa, and now Dean was being hailed as the new Clift and Brando. Despite avoiding his advances and admiration, both Brando and Clift had unwittingly helped launch Jimmy Dean’s career.

In East of Eden, Dean gives an incredibly intense performance as Cal, the tortured antihero that both his heroes had turned down playing. I think everything you need to know about James Dean’s talent (and the enormity of his lost promise) is contained in this performance.

Cal is inarticulate and tender. He has a masochistic streak. He acts on instinct – other characters liken him to an animal. Cal does everything wrong because he cares so much. He’s ultimately a romantic figure in his desperate desire to connect. He glances away, uncertain. He’s full of contradictions. He’s painfully human. We learn all this in the film’s first few scenes.

Cal first appears on the street, sitting on the curb, shoulders slouched forward. He’s discretely watching the woman he believes to be his mother (Jo Van Fleet) passing by on her way to make a deposit at the bank. He watches her from across the street and eventually follows her back to her home, which is also her workplace. It’s a brothel and she’s the town madam. Cal and his twin brother, Aron (Richard Davalos) believe she died after they were born. This is what their father, Adam (Raymond Massey) told them when she took off.

She won’t talk to Cal so he leaves Monterey and hitches a ride on the roof of a cargo train across the Santa Lucia Mountains to his home in Salinas. In a quite extraordinary scene, he wraps himself in his own sweater, wearing it like a strait jacket, crying and chastising himself for not just going in there to talk to her. I’ve always wanted to know whether this action was in the script.

We meet Aron and his girlfriend Abra (Julie Harris). Aron tells her that Cal wasn’t home all night and that he’s going to get it from their father. Abra says, ‘You know what the girls in class call him? The Prowler.’ And he does prowl – following them to the icehouse their father has bought for a new business venture refrigerating lettuces to transport east. Cal hangs back in the scene when his father is talking to another businessman – he’s the focus of the frame despite occupying a peripheral position. It’s clever composition by Kazan – magnifying the distance between Cal and his father that’s highlighted when his father dismisses his idea about planting corn and beans instead.

In the icehouse, Cal prowls again as Aron and Abra talk about him. Aron ecstatically admits, ‘I love him.’ Abra says she find him ‘scary … When he looks at you. Sort of like an animal.’ There is more than a hint of exhilaration in her voice at this observation.

The intimacy between Aron and Abra has an effect on Cal, who clearly wants some of what they have for himself. He becomes increasingly upset, knocking ice blocks over and eventually running out. Because he’s shut out from love, his primal instinct is to destroy everything in front of him. His body becomes a weapon and maybe even his enemy.

Dean is constantly loose and limber in these early, establishing scenes. Even when he stands still, you can sense the movement about to come, a kinetic energy that sparks each frame he’s in. These movements convey everything about his character.

Cal’s tortured by a desire to please his father and the wounds of their alienation from each other. Later, his father tells him, ‘You are through and through bad,’ and Cal has started to believe it, ‘It’s true … Aron’s the good one.’ Cal pleads with his father, literally wrapping his shoulders across the table, to tell him about his mother, ‘I’ve got to know who I am. I’ve got to know who I’m like.’

The pose is echoed in the following scenes when Cal again escapes to the brothel in Monterey and pleads, bent across the counter, with the bargirl to show him where his mother Kate is. Cal’s posture reveals his longing more completely than any of the dialogue escaping his mouth. The pleading posture continues when he kneels before his mother and attempts to talk to her. He’s looking for a reason why he’s ‘no good’ – he thinks she’s it.

Time moves on and things seem to change. Cal tries to help his father so goes to see his mother to ask her for some money. In her office, he sits across from her and pleads his case, fidgeting in the chair, shoulders hunched, leaning forward. As the conversation switches from money to questions about the past, Cal stands, head forward, eyes lowered. When she gives him a cheque, Cal lingers, leaning forward, yearning for something more, but despite telling him he’s a ‘likeable kid’ she asks him to leave reminding him that she is running a business.

Later, there’s a fair and Cal entertains Abra as she waits for Aron to arrive. Stuck together on the Ferris wheel, Abra wonders whether Aron really loves her. Cal listens, patiently. When she touches his hand – the first physical contact he has had with another character in the film – he melts. His shoulders relax and they kiss. But then overcome with guilt they turn from each other and Cal’s shoulders curve inwards once again.

Pauline Kael described Dean’s role in East of Eden as a new image in American film, ‘the young boy as beautiful, disturbed animal, so full of love he’s defenceless.’

There was apparently no love lost between Dean and Massey. This mutual dislike served the film well. As Kazan noted,

The screen was alive with precisely what I wanted; they detested each other. Casting should tell the story of a film without words; this casting did. It was a problem that went on to the end, and I made use of it to the end. (Kazan on Directing, 2009, p185).

This ‘problem’ is apparent in the film’s most powerful scene. After making the money his father lost on the lettuce business back, Cal (with Abra’s help) organises a party for Adam’s birthday. They decorate the house. Cal is nervous and eager to please; he can barely keep still. When Cal gives his father the package of money, Aron steals the moment by announcing his and Abra’s engagement. And Adam walks away from Cal, yet again.

Abra reminds Adam that he hasn’t opened Cal’s present yet but he says, ‘I can’t imagine having anything better than this.’ He is displeased by the gift of money, but Cal insists, ‘I made it for you … I want you to have it.’ Adam tells him he has to give it back to the farmers he’s ‘robbed’. Cal’s devastated and hunches down, crying, practically lying on the dining table. As he rises he turns to Adam, and shoulders curved, tries to hug him. Receiving no response he leaves the house wailing ‘I hate you.’

It’s an extraordinary scene because men on screen at this time just didn’t do that. The vulnerability on display here remains overwhelming no matter how many times you’ve seen it.

Dean enters Rebel Without a Cause with a similar challenge to convention, in a passive pose, lying on the floor drunk. When Jim cries, ‘You’re tearing me apart!’ to his parents, it’s his body that’s the battleground. You can feel that howl coming from somewhere deep in his belly. Along with Brando in The Wild One (1953) and the emergence of Elvis Presley (a huge fan of Dean’s) in 1956, James Dean’s performance in this film signalled a milestone in ideas about what it meant to be young, but more importantly, how young men were represented in popular culture. As Roger Ebert notes, ‘they could be more feminine, sexier, more confused, more ambiguous.’ Much of this is expressed throughout Rebel in Jim’s tough yet soft relationship with Plato (Sal Mineo).

What made Dean’s nonconforming physical presence different is most obvious in Giant – in the contrast between his defensive shrug and Rock Hudson’s square-shouldered dominance. His restless movements, his neediness and vulnerability, saw him steal the film out from under its two apparent stars (Hudson and Elizabeth Taylor). As Jett Rink, Dean is an outsider – a solitary figure who has no one and wants what he cannot have. He lurks on the fringes of the Benedict family’s life and land, prowling around, again. There is something quite discomfiting about Dean’s performance. It is, at times, nerve-wracking to watch. I mean this as a compliment.

According to Kazan the shrug was Dean’s ‘natural’ mode of expression. And I believe him. It isn’t just a feature of Dean’s three distinct screen personas; it’s also visible in most of the photos that were taken of him in his short life – his way of moving through the world.

Roy Schatt also took photos of James Dean. Best known among these are the gorgeous ‘Torn Sweater’ series shot on December 29, 1954, at the request of Life magazine, although they never ended up running the pictures. Schatt was a friend of Dean’s and also his photography teacher.

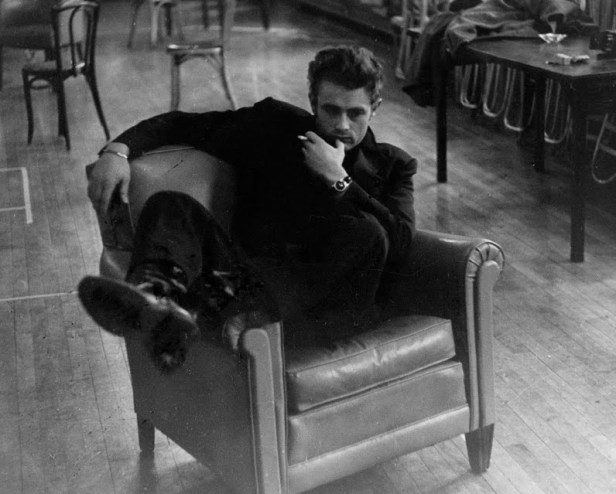

Schatt took these photos of Dean too, lounging around – brooding, languid and erotic. They are an interesting contrast with Stock’s images of Dean as a wholesome Midwestern farm boy. Here, he lies around waiting for something, absently running his fingers through his hair, curving his fingers sensuously around his cigarette. He seems incapable of sitting in a chair in a normal way.

James Dean’s was a brief but brilliant career – especially his work in East of Eden. While many have said his talents are exaggerated and that he died before they could really be tested, before he could fail, before he could grow up (thanks for that profound insight Donald Spoto), I believe that James Dean still matters. Sometimes it’s been a struggle to say anything about him that hasn’t been said before. But for me, everything I’ve written is true.

James Dean’s was a brief but brilliant career – especially his work in East of Eden. While many have said his talents are exaggerated and that he died before they could really be tested, before he could fail, before he could grow up (thanks for that profound insight Donald Spoto), I believe that James Dean still matters. Sometimes it’s been a struggle to say anything about him that hasn’t been said before. But for me, everything I’ve written is true.

It was a short career, but a legend that casts a long shadow in multiple directions. Robert Altman’s 1982 film, Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, based on the 1976 play by Ed Graczyk, shows us the extent of this idolatry. The narrative focuses on an all female fan club called the Disciples of James Dean, who meet inside a Woolworth’s Five-and-Dime store in Texas in 1975 to the commemorate the 20th anniversary of his death.

This is just one film but he’s everywhere in popular culture. Just think about all the songs (other than ‘Rock On’) that name check James Dean (some of them good, some of them not so good): ‘Jack and Diane’ by John Mellencamp, ‘Vogue’ by Madonna, ‘Electrolite’ by R.E.M, ‘American Pie’ by Don McLean, ‘Blue Jeans’ by Lana Del Ray, to name but a few.

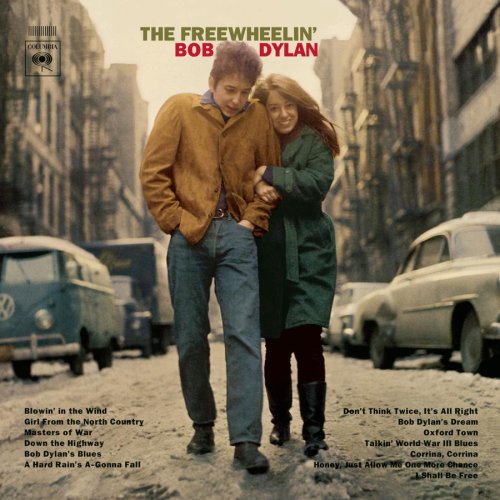

Bob Dylan has never written a song (directly) about him but James Dean was his first idol. He was obsessed with him after he saw Rebel Without a Cause. It’s pretty clear that Dean’s ghost haunts Dylan’s Sixties style – it’s there on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), which recreates the setting and hunched pose of ‘On Times Square’ and the Schatt photo below with Dylan in a beige version of the red Rebel windbreaker. Dylan has said he liked Dean for the ‘same reason you like anybody, I guess. You see something of yourself in them.’ The cover photo of Dylan’s memoir, Chronicles: Volume One (Simon & Schuster, 2004) is a black and white photo of Times Square in the 1950s that seems to link his journey with Dean’s. As McLean sings in ‘American Pie’, Dylan’s coat was ‘borrowed from James Dean’ and all you need to do is watch Don’t Look Back to see that Bob had Jimmy’s effortless cool.

There’s more. Without Dean we wouldn’t have Morrissey’s quiff. We wouldn’t have modern-day hipsters in oversized prescription glasses and cardigans. (Dean was terribly near-sighted and wore very thick glasses when he wasn’t on screen. He wasn’t trying to be cool.)

Without Dean we wouldn’t have the annual unveiling of ‘The New James Dean’ – think Johnny Depp, River Phoenix, Colin Farrell, James Franco, and Robert Pattinson. We wouldn’t have vulnerable performances like John Cazale’s in The Godfather and The Godfather Part 2, like River Phoenix’s in My Own Private Idaho, like Leonardo Di Caprio’s in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? and The Basketball Diaries, like Mickey Rourke’s in Rumblefish, or Heath Ledger’s inarticulate sensitivity in Brokeback Mountain.

James Dean may be remembered by most as a moody poster boy for living fast and dying young, but he was much more. His performances were honest, true and deep. In that brief time when he made films, there was no one like him. Maybe he took personal pain and turned it into something beautiful in those three performances. Maybe his shoulders tell us something about this struggle, if we are prepared to look closer.

It’s there in the photos too. In ‘On Times Square,’ he’s battered by the elements but also resilient to them. But if Dean looks beat – as the New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik has commented, like he’s ‘bearing the weight of a generation on his shoulders’ – maybe it’s just because he was tired. Dean was an insomniac; you can see it in his face, which always looks more drawn than it should at 24 years. Maybe he leans forward, towards us, because it was just too exhausting for him to stand up straight.

In the end, what I really like is the way the expressiveness of Dean’s body links sensitivity and vulnerability with strength. He shows us something quite different about being a man. There is sexiness in his languor, passivity and femininity, and he is immensely desirable. The curve of his shoulders is a move towards an embrace, a folding of the body into repose, a willingness not to fight. Even when he’s angry, he’s gentle. He acted with his entire body, not just his voice and his face. That may not mean much today but in the history of American film it means a lot. It’s not an overstatement to say that how James Dean moved on screen changed things. And anyway, I don’t mind the occasional overstatement.

love this

Thanks! Love that you love it.

Wicked! Churps, always a good read

Cheers! Thanks.

loved this so much, I really wanted to say something smart like you in your post, but I can’t, so that’s it hahaha but I really loved it

Letting me know you loved it is more than enough. Thanks so much.

Beautifully written as always, feels so intimate despite the research. Love the pics. Had a French friend in the late 80s who looked just like JD. Still alive though … Take care Jo.

Phil

nice … but I think James Franco did a pretty incredible job of portraying JD …of course JD had a look unique to him but so does everyone I believe

He wasn’t bad at all, although any film about Dean is going to be a strange experience. I agree with what you say that we all have a unique look.

Read several articles on James Dean but none of them echoed as closely with my own sentiments, as much as yours. Beautifully and honestly written. Thank you 🙂

That’s a very kind and generous thing for you to say. Thank you and thank you for reading.

I really like your article, very well written and wonderfully descriptive of James Dean. I to am a long time Dean fan but since I saw Rebel without a Cause at age 6 or 7. Thank you for writing this, it now has me re-looking at James Dean’s pictures.😄

Thanks Tammy. This was one of my favourite pieces to write and one I like to revisit from time to time. So many wonderful, beautiful photos out there – enjoy!