It happens, at the film’s halfway point. The whole film is leading up to it. It’s an unpretentious scene in which arguably the two greatest actors of their generation, finally, share the screen.

We’ve been waiting a long time for this. Maybe they have too.

And it all begins like this:

Vincent Hanna: What do you say I buy you a cup of coffee?

Neil McCauley: Yeah, sure, let’s go.

Hanna: Follow me.

It’s Michael Mann’s blue-lit crime epic, Heat (1995) – the film where two stars whose careers have followed a similar trajectory finally collide. It is the film’s pivotal dramatic moment. Famously, both starred in the greatest of all sequels – The Godfather Part II (1974) – but never had a scene together. Mann gives them a sublime moment – Al Pacino and Robert De Niro sit down for a cup of coffee, sharing an off-screen history, respect and a secret language, like two boxers in the ring.

Mann’s film presents an archetypal conflict between a cop and a criminal. Pacino is Lt. Vincent Hanna, an obsessive detective with the Los Angeles police department whose wife has to share him with ‘all the bad people and all the ugly events on this planet.’ De Niro is Neil McCauley, an emotionally detached career criminal whose done time but has one major job left in him before a retirement of sorts, to Fiji, maybe, to a quieter life. Throughout Heat these men engage in a tense game of cat-and-mouse, often staged with the grandeur of opera, that keeps us on edge from beginning to end. Our allegiances shift and sway the closer we get to them and the closer they get to each other. It’s a taut, edgy, stylish film, so much more than the sum of its parts because of the presence of these actors.

I wrote about Heat in one of the chapters of my doctoral thesis, which looked at anxiety over masculinity in the films of the Clinton era. For me, Heat is more than a crime film. And it definitely isn’t an action film, well maybe only in the strictest sense of the genre. In my thesis, I argued that Heat is ultimately about inaction – about two men forced to stand still and take a good look at themselves as they wrestle with the internal question of what it means to be a man. Mann reinvents the crime/action film with an atmosphere of melancholy nostalgia for a very particular way of being male in America.

I also argued that Heat is a Western because of its use of landscape and space to say something about character and identity. Westerns situate lonely heroes in symbolic landscapes. Rather than a duel in the sun, these men do existential battle against a noir backdrop. Heat’s electric LA skyline is swathed in a cool blue canvas of light and shadow that reflects a tightly controlled world – like its wounded heroes, this is a world on the verge of collapse. It’s a moody urban terrain, glamorous and grimy, yet minimalist enough to recede behind the unfolding drama of men under pressure. McCauley’s personal landscape, his house, is austere and sterile, furnished with only the basics. It’s the very embodiment of his personal philosophy: ‘Have no attachments. Allow nothing to be in your life that you cannot walk out on in thirty seconds flat if you spot the heat around the corner.’

Landscape reduces right down in the coffee shop scene where Pacino and De Niro come face to face for the first time.

The anticipation of seeing these two iconic actors together, both now in middle age, is drawn out until the mid-narrative point. When it happens, there’s nothing showy. Some viewers might even find it underwhelming, anti-climactic. But maybe that’s the point. The scene is tight, nuanced and very natural – just two men sitting down and talking.

Mann delays our gratification, funnelling it into a non-confrontational encounter heavy with psychological intimacy rather than spectacular feats of acting prowess. On De Niro’s suggestion they didn’t rehearse the scene together. They learnt their lines and showed up and did it, allowing them a chance to play off and respond to one another in a less structured way. To do what Stella Adler might have told them – ‘don’t act, behave.’

The coffee shop scene, the coming together of these titans of American screen acting, magnifies the existential crisis at the core of the film. Simply, in this brief exchange, over the ordinary act of drinking coffee, each man recognises and admits that what they do is more alike than dissimilar. There is also a reluctant respect and admiration for their dedication to the ‘job’. Coming face to face with each other, they confront themselves.

There are sparks here but they are contained. It’ll be a fight to the death between these two, but for now, it’s just a cup of coffee in one of those brightly lit, noisy Los Angeles spaces. Neither man has anywhere to hide.

Hanna’s been following McCauley on the highway when he suggests the coffee date. Hanna is defined by the chase – he sniffs out his prey, captures him and hopefully brings him to justice. As he tells his neglected (third) wife, Justine (Diane Venora), ‘All I am is what I’m going after.’ He carries the angst of his job with him wherever he goes because ‘it keeps me sharp, on the edge, where I gotta be.’ McCauley is also indistinguishable from his ‘career.’ His criminality requires him to live by a strict moral code that sees him sacrifice human connections.

While each man recognises that they are on opposite sides of the story, they also see that their paths are inextricably linked. As McCauley explains, ‘I do what I do best. I take scores. You do what you do best. Trying to stop guys like me.’ What is revealed as they share further details about their lives is that the gap between them is in fact a narrow one.

Each man, in his own way, is a workaholic – defined almost exclusively by what he does. Neither man wanted a regular life with barbeques and ball games; neither bought into that version of the American Dream. Hanna can’t grasp the possibility of anything else, admitting, ‘I don’t know how to do anything else.’ McCauley agrees, ‘Neither do I.’ More importantly, neither wants to. If ‘the action is the juice’ when the action’s over, what’s left?

The coffee shop scene is a great scene on so many levels. I could keep going, but I want to move on. The only thing wrong with the scene, as far as I’m concerned, is that it doesn’t go on longer than it does. It’s significant too for reminding us of the story that Pacino and De Niro share as part of American film history. Pacino and De Niro’s careers mirror each other – each giving us, in their best moments, invaluable lessons in Method acting.

When Heat was released, many critics praised Pacino for matching De Niro’s cool control. Others critiqued him for not being as restrained, for ‘booming’ and ‘exclaiming’ his way through the film. British critic, David Thomson, while a fan believes that if the scene is an acting master class,

De Niro wins hands down because he takes a cue from every bit of bluster and heavy breathing in Pacino. He does less and waits like a snake. De Niro is, and has always been, the fiercer and more mysterious actor, the one less anxious to be liked.

I’d say this is unfair. Sure, De Niro does less here – he has less dialogue. He’s cool and lean and charming – his character throughout the film the very embodiment of the strong, silent type, the quintessential loner. I think Pacino keeps the bluster to a minimum in this scene – his delivery is focused, intense and emotional. Actually, I think he keeps a lid on it for the film’s whole three hours. When he’s explosive, it’s cause he needs to be. Pacino being Pacino is all in service to the script.

But Pacino’s acting is not all grim according to Thomson, who concedes that his Michael Corleone ‘is one of the central double-shot performances in American film’ (more on that below) and that in The Godfather Part II (1974) De Niro learned not only from Brando (who played the same role in the first instalment) but also from the ‘frozen, settling calm of Al Pacino, playing his son.’ This description is a far cry from the frenzy Thomson suggests has become a feature of post-1970s Pacino. But in the coffee shop shoot-out he anoints De Niro the victor. Who knew it was a competition?

While I can understand some of the criticism hurled Pacino’s way in recent years for crimes against the Method (I prefer to point to a film like the dreadful The Devil’s Advocate (1997) or cheesy Scent of a Woman (1992) rather than Heat), a complete dismissal of his continuing importance is unfounded. Such critics clearly haven’t seen Carlito’s Way (1993), Donnie Brasco (1997), The Insider (1999) or Insomnia (2002). And while it’s not strictly a film (as in a cinema release), Pacino’s performance in HBO’s extraordinary Angels in America (2003) as the closeted Roy Cohn (his scenes with Meryl Streep’s Ethel Rosenberg are among my favourite scenes from pretty much anything in the past decade) is one of his finest.

It’s good to see that Thomson doesn’t let De Niro entirely off the hook, suggesting that in later years he seems to have been motivated by pay checks and pointing to atrocities such as The Fan (1996) and Frankenstein (1994) as major low points in an otherwise stellar career (he forgets The Adventures of Rocky & Bullwinkle and the ham-fest that is Analyze This and That). Thomson decides that while ‘they’ve both overdone it in their time to the point where it’s a bit of a joke’ they can afford to ‘trade on our fondness and forgiveness.’

And how can they not? Perhaps their greatest roles are behind them, maybe have been for quite awhile. Does this matter? All the great actors made some bad movies (Brando included). But amidst the bad over the last couple of decades has been some good too – for Pacino, the neglected films I mention above, plus Glengarry Glen Ross (1992) and Any Given Sunday (1999); for De Niro, Casino (1995), Wag the Dog (1997), Jackie Brown (1997), This Boy’s Life (1993) and 2006’s The Good Shepherd (which he also directed).

In the end, it’s not difficult to forgive Pacino and De Niro anything, really, when you remember that these are the actors who gave us some of the most iconic performances of the 1970s and early 1980s – performances that define an era and which I am sure up and coming actors continue to measure themselves against.

Maybe it is a competition. They were always going to be compared to one another. Both trained in the Method – Pacino at the Actors Studio under Lee Strasberg, De Niro with Strasberg and then at the Stella Adler Studio. They came up together, Pacino a few years older and a few years ahead. Both starred in a string of films no one saw before they landed roles in films no one could ignore.

And it all culminated with the Godfather phenomenon – a moment, at the beginning of a decade where American cinema changed all over again. Pacino and De Niro loom large over the 1970s in roles that remain integral to the cultural influence of American cinema today.

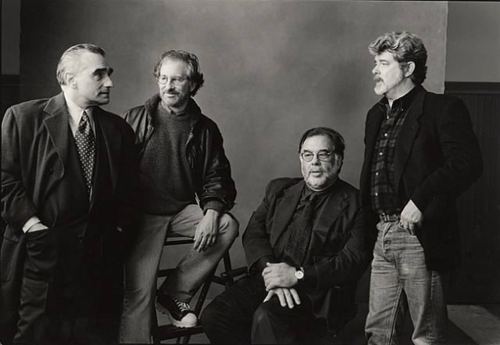

What a decade it was. The 1970s was bursting with outstanding films and breathtaking performances. It’s the decade where the American auteur took control of the camera. Dominating the 1970s were a new breed of directors, some fresh out of film school, ready to remake American film from the ground up. Heirs of the New Hollywood born in 1967 with the release of Bonnie and Clyde (dir. Arthur Penn) and The Graduate (dir. Mike Nichols), I’m thinking in particular of Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Brian De Palma and Steven Spielberg – as Peter Biskind has described them, the ‘easy riders and raging bulls’ who made Hollywood exciting again. (Of course, this list should also include John Cassavetes, George Lucas, Peter Bogdanovich, Robert Altman, Woody Allen, Terence Malick, Roman Polanksi and William Friedkin.)

On the one hand, the 1970s are dominated by De Niro’s work with Scorsese. One of the most significant partnerships in the history of cinema began in 1973 with Mean Streets, continued with Taxi Driver (1976) and peaked with his shape-shifting role as Jake La Motta in Raging Bull (1980). Add to that his overshadowing role in The Deer Hunter (1978) and talking Italian in The Godfather Part II as the young Vito Corleone, and you have a body of work that anoints De Niro as the rightful heir of Brando. Few can deny that De Niro’s work in Taxi Driver and Raging Bull are two of the most astonishing performances ever committed to celluloid. Every time I watch them I find something new to marvel at. Great roles continued with Scorsese in the 1980s and 1990s – the underrated discomfort he caused as Rupert Pupkin in The King of Comedy (1983) and his solid support in Goodfellas (1990) stand out from the pack.

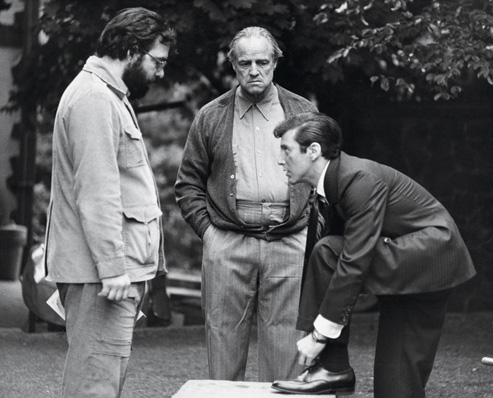

On the other hand, the 1970s are also dominated by the figure of Michael Corleone. It’s now well known that Coppola had to fight Paramount Pictures to cast the relatively unknown Pacino. Robert Evans, the Senior Vice-President in Charge of Worldwide Production (yes that was his full title at the time!), wanted a star – Robert Redford, Warren Beatty or Ryan O’Neal. He thought Pacino too short, ugly and unglamorous. With hindsight one might ask – was Paramount being run by idiots. Let’s not forget Evans fought against the casting of Brando too.

Coppola’s persistence paid off. (The film also saved the studio financially.) Watch The Godfather (1972) and then Part II back to back to witness how Pacino slowly builds Michael from the ground up into the menacing head of the Corleone family. When we first meet him at his sister Connie’s wedding he’s innocent yet knowing. He’s a war hero and a Dartmouth graduate who identifies at a distance from his family’s business. As he tells Diane Keaton’s Kay, ‘That’s my family … not me’.

Circumstances take over, maybe fate, and Michael is drawn in when his father, Don Vito Corleone (Brando) is shot and wounded. As the Don lies in hospital, a meeting is set up in a restaurant in the Bronx with the culprits – the rival mafioso, Sollozzo and his ‘bodyguard,’ the corrupt cop Captain McCluskey. A weapon is planted in the restaurant’s toilet and Michael is instructed by his father’s loyal henchmen Tesio and Clemenza about how it’s going to go down. This is a whole new world for him and we see him caught between a sense of duty and downright fear. As he sits down to dinner with them and looks for the right moment to excuse himself, Pacino makes the tension in this scene palpable. You can see it in his body, held tight like a spring about to snap. If you haven’t seen the film before you will be wondering whether he gets out alive and if you have seen it you’ll notice anew how this is the point where it all changes for him.

By the end of Part II, guilty of ordering the murder of his brother Fredo (John Cazale) and estranged from Kay (from whom he has taken their children), Michael embodies the absolute worst that his family represents. Pacino gives him a dead cool expression that first surfaced at the end of Part I, when the doors close on Kay as he is greeted as godfather. His menace is in his stillness. There is such extraordinary layering and depth here that there is little wonder that Michael is a character audiences feel ambivalently towards. The ending of Part III (1990) mirrors the profound conclusion of Part II where Michael sits alone outside at the Lake Tahoe compound, at the bottom of an amoral abyss, remembering happier times when his brothers and his father were alive. He ends his days alone – a tragic figure rather than a definite villain.

Looking at his filmography, it is true that the 1970s were Pacino’s finest decade. In addition to his work in The Godfather films, there are his dynamic performances for Sidney Lumet in Serpico (1973) and as Sonny Wortzik in Dog Day Afternoon (1975). He was nominated for the Best Actor Oscar for both. He should have won for at least one of them. Taking another look at these films in relation to what he does with Michael Corleone it’s easy to see what makes Pacino great – the physicality, the ability to observe and swallow a scene whole, the nervous tension buzzing through him head to toe, a character’s entire story there in those huge brown eyes. It’s still there in Heat.

By the time the 1970s were over, De Niro had a Best Actor Oscar for Raging Bull and was a movie star, while Pacino had taken a more ‘arty’ path to success with films like Bobby Deerfield (1977), … And Justice for All (1979) and Cruising (1980). As the 80s progressed, Pacino made fewer films, taking extended breaks and continuing to work in theatre, exploring his love of Shakespeare. He won his Oscar (in 1993 for Scent of a Woman) for the wrong film.

I can’t help thinking of Norma Desmond’s exclamation in Billy Wilder’s wonderful Sunset Boulevard (1950), ‘I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.’ There is some truth about the quality of scripts Hollywood is churning out, particularly for actors of a certain age group, of which Pacino and De Niro are now members.

I’d rather not have to choose between them – it’s like trying to choose between vodka and gin, vanilla and chocolate. I’d rather there wasn’t a showdown. Like their characters in Heat they are more alike than dissimilar. For me, Pacino and De Niro will always be part of the same family (not just Corleones) but as David Thomson calls them part of ‘the Brando triangle’ – brothers who learnt not only from the master of the Method but also from each other that great acting is a journey within.

* Pacino and De Niro reunited in 2008’s Righteous Kill (directed by Jon Avnet) playing veteran cops. I haven’t seen it hence why I haven’t discussed it, and anyway the spotlight’s on Heat here.

I definitely agree on this. The seventies was a golden period of francis, spielberg, scorscese & Lucas. Lucas was more known for his fantasy extrvaganza “star wars” while spielberg was breaking the mould by following later with “Schindlers list” though 70s was rocked by “Jaws” well enough. Recently i was completely intrigued with Al Pacino and for entire 2 weeks i was on Pacino movie marathon. Starting with Godfather 1 & 2, Godfather 3, Scent of a woman, Justice for all, Dog day afternoon & Serpico. The chronology was a bit missed here i suppose. But i really dont agree that it was a wrong oscar won for Scent of a Woman. This doesnt imply that AP shouldnt have won it before but i still feel that the entire streak of Al pacino’s performance was of an angry young man. For me justice for all & Serpico fell on same league the style though great was same. So It started with godfather and ended with Justice for all in 1979. Lt Col. Slater broke this cast primarily still carrying his ruggedness. It was sheer performance of Al pacino – his voice modulation, his saying Woo-ah!!, his abuses, his cold blind stare!! everything for me was mesmirizing. And who can forget the last stand he took in the Baird School. Come on !! It was satisfying for a brat like me who has being fan of Method acting. Something which i will certainly adopt if i become an actor.

Great comments, and all completely relevant and true. To clarify, it isn’t so much that I think Pacino’s performance in Scent of a Woman was terrible, just that I feel like he should have received Oscars earlier in his career, for any one of those other films you mention. Much like I don’t think The Departed is Scorsese’s greatest film (it is great, though). But definitely difficult to go past his performance in The Godfather trilogy and the way he builds that character from wide-eyed, knowing but hopeful, into a thing of chilling menace. So so so brilliant!

Exactly, I agree Godfather 2 was a perfect Oscar heaven for AP but sadly it didnt happened. Martin Scorscese for “The Departed” was never the right choice and many like me feel that it was given to correct some mistake. Nevertheless it happened and we are past through it. This makes me remember when A R Rehman got the Oscar for music arrangement in “Slumdog Millonnaire” it was never his best work even to which he also agreed later. I have grown up listening to his music!! He is a maestro!