Rock Hudson was not the greatest actor of all time. When compared to the on-screen gifts of many of his contemporaries (yep, Brando, Clift and Dean again) he was one-dimensional in the classic Hollywood style.

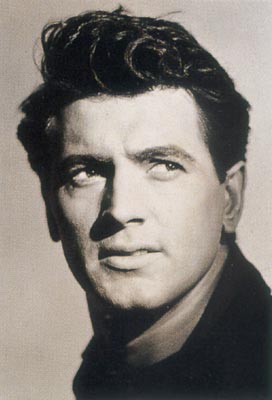

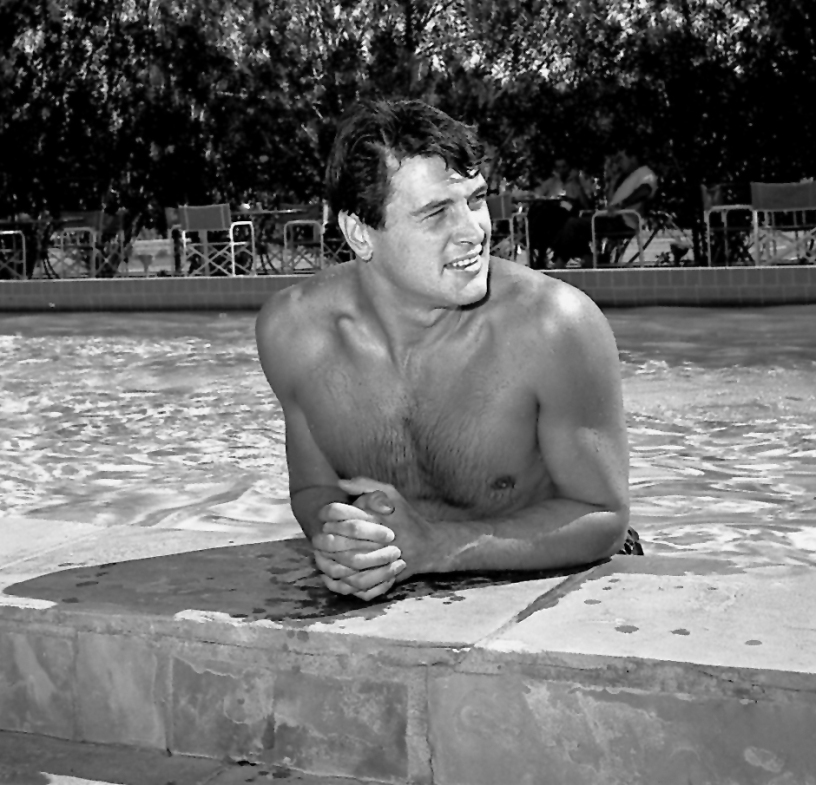

But Rock Hudson was a good actor, sometimes very good. And he had something from the start that is certainly in short supply today – screen presence. He really filled up a screen. Hudson is always a pleasure to watch – that handsome face, that broad chest, the deep, velvety voice and the rather dazzling smile. Hudson was that rare Hollywood entity, a class act and bona fide leading man who could do a bit of everything – Westerns, melodramas and romantic comedies.

Rock Hudson was born Roy Harold Scherer, Jr on November 17, 1925. At 6 feet 5 inches, Hudson was large, solid, still, like a rock, like the name his agent Henry Wilson conferred on him in 1948. As we all now know, Rock Hudson lived the majority of his public life in the closet. While it was apparently no secret to Hollywood insiders and his closest friends that Hudson was gay, he worked within a star system that regularly rewrote an actor’s personal narrative to match what movie audiences seemed to crave and find most palatable. Being a homosexual did not fit this script.

Henry Wilson was also gay and made his name cruising clubs looking for talent, for both his personal and professional use. He gave his clients new names and new life stories that included conventionally masculine pursuits such as football or fishing. He rid them of any visibly queer traits – limps wrists were straightened up and lessons were provided on how to light a cigarette ‘like a real man’, with one swift single motion.

Hudson’s new identity, as Rock, built on his natural charm and hunky body, his mid-Western roots and his wholesomeness. His old identity flowed into his new one – how easily we’ll never know, although Hudson’s years of heavy drinking would suggest a private struggle.

Hudson’s public or Hollywood persona (the star persona constructed by his films and his publicity) was initially defined by his solidity, constancy and dependability. This persona was also inextricably tied to his body.

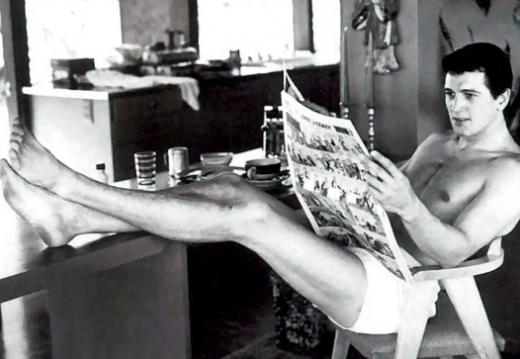

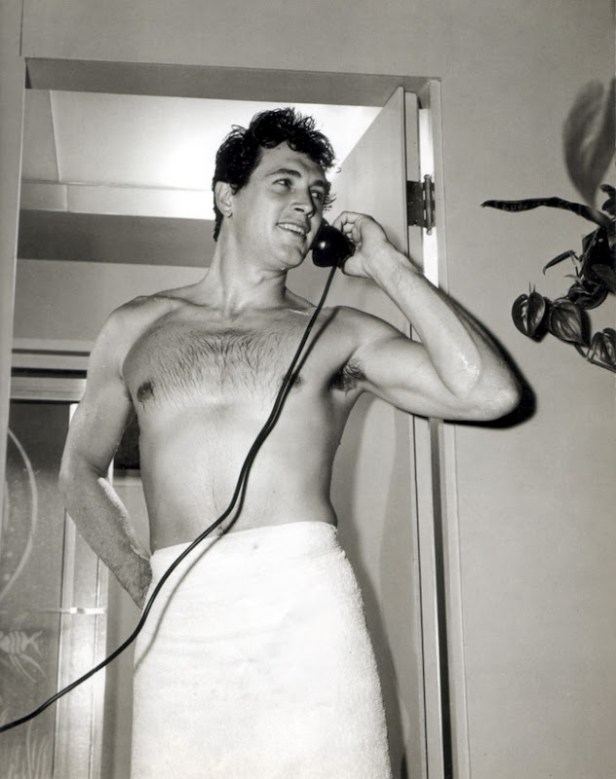

In the early 1950s, Rock Hudson’s public persona was built through a series of photo shoots for magazines. A famous shoot in 1952 for the Saturday Evening Post offered up photos of the then 27-year-old Hudson in a variety of poses that reinforced his regularity and dependability – washing his car, listening to Sinatra, eating eggs. In some photos he is in rather middle-aged cardigans, in others he is half-clothed in shorts reading the newspaper and on the phone, wet from the shower in nothing but a towel, revealing his rather lovely body. In photo shoots like this one, Hudson is both a figure of strapping, manly desire and of nonthreatening middle-class normality.

Hudson was Wilson’s most successful product and the agent worked hard to make sure he remained profitable. As Hudson became more visible the public wanted to know when ‘Hollywood’s Most Eligible Bachelor’ would marry. Pressure mounted when the LA scandal rag, Confidential, threatened to leak a story (complete with photos) about Hudson’s secret life that could have destroyed his fledgling career. Wilson and the might of the studio stepped in, orchestrating the first of Hudson’s two short-lived, sham marriages – to Wilson’s secretary Phyllis Gates in 1955. Magazines reported a whirlwind romance, true love. Despite the flimsy nature of the tale, the public bought it, as they say, hook, line and sinker, because they wanted to.

The public persona manufactured by Hollywood through magazine articles and photo shoots supported and bolstered the identity Hudson was beginning to express through his film roles. But it also had its limitations.

Hudson’s career began with a series of unimpressive performances in the late 1940s and early 1950s – his first in the war drama Fighter Squadron (1948) required 38 takes for him to deliver a single line. But it was his role in Douglas Sirk’s 1954 film, Magnificent Obsession that made him a star, and cemented him as a leading man of substance. If Hudson’s early career was a little colourless and inconsequential, too reliant on his regularity, his work with Sirk (they made five films together) changed all that and pushed his image in another direction. Sirk cast Hudson against type and as a result turned the wholesome, all-American boy into a more interesting and seductive character – a romantic leading man.

Sirk was a master of the woman’s picture or melodrama. Loosely defined as a genre that portrays women’s concerns – that is, films revolving around the problems of domestic life, the family, motherhood, self-sacrifice and love – these films feature female protagonists and are designed to appeal to female audiences. The genre peaked in the 1940s and 1950s, with films directed by Sirk, George Cukor, Max Ophuls and Josef von Sternberg. Its most prolific stars included Joan Crawford (The Women, Mildred Pierce), Bette Davis (Jezebel, Now, Voyager), Barbara Stanwyck (Stella Dallas) and Sirk regular, Jane Wyman.

Known for his lush, touching narratives, Sirk’s cinematic canvas bursts with characters that require empathetic actors to convey the full spectrum of their emotional lives to the audience. This is certainly true of Magnificent Obsession, which despite its preposterous story arc, is a deeply affecting film predominantly due to the beautiful performances of its two leads – Hudson as the reformed playboy Bob Merrick and Jane Wyman as Helen Phillips, the woman whose life he first ruins and then redeems. It’s an exquisitely lush film and because of Hudson and Wyman you can’t help being swept up in every melodramatic moment.

Because of their tendency to go over the top, Sirk’s films were not well received by critics at the time of their initial release. A process of revision began with Jean-Luc Godard’s Cahiers du Cinema piece on Sirk’s 1957 film, A Time to Live and a Time to Die. Rather than a director of ‘weepies’ (the idea being that films about women made for women were of less value and not meant to be taken seriously), Sirk is now seen as a supreme commentator on the complexities and hypocrisies of American life in the 1950s – the perils of conformity, gender, class and racial issues, the quiet desperation simmering in the suburbs.

Sirk’s thematic and visual influence is evident in Todd Haynes’ wonderful 2002 film, Far From Heaven, an unironic tribute to both All that Heaven Allows and Imitation of Life (1959). Haynes was able to engage directly with many of the issues that Sirk could only begin to lift the veil on and in doing so reminds us of the importance of this director’s work.

The masses were ahead of the critics on this one. Audiences, especially women, always loved Sirk’s films. Soon enough they fell in love with Hudson too.

Rock Hudson’s broad chest plays a key role in my favourite of his collaborations with Sirk, 1955’s All that Heaven Allows. Here, the landscape of the film has a close relationship to the ‘landscape’ of Hudson’s body.

Hudson, the rock, the ‘man mountain’ as some named him, is linked to nature throughout All that Heaven Allows. His character, Ron Kirby, cultivates trees and takes care of the gardens of the rich. He is earthy, sensual and unpretentious. Grounding his characters in a more tangible social reality than Magnificent Obsession, in All that Heaven Allows Sirk presents Ron as the most ‘normal’ character in a world populated by inauthentic consumers concerned with keeping up appearances above all else.

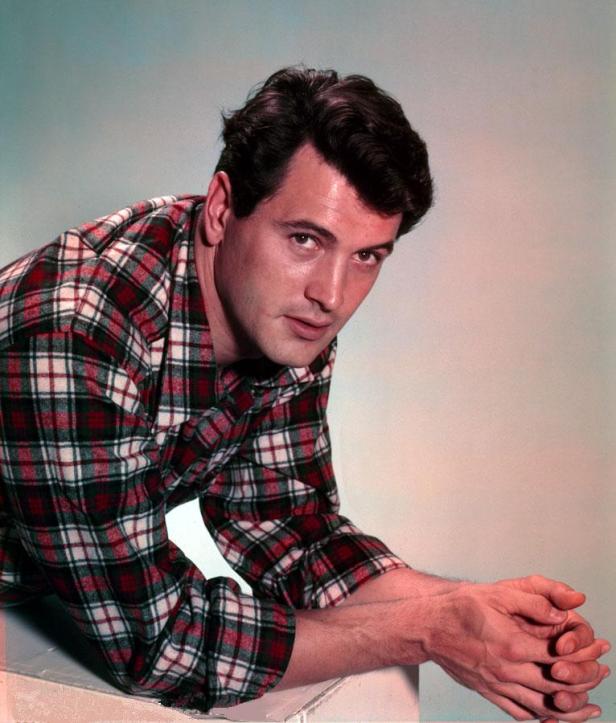

Ron wears flannel and lives a life closely modelled on the transcendental philosophy espoused by Henry David Thoreau in Walden. Ron literally goes to the woods to live, to live simply and deeply and put to rout all that is not life. Jane Wyman’s character Cary Scott is a widow. The younger Ron offers her the promise of a new life, an alternative to the endless cocktail parties and hollow country club soirees.

Sirk’s compassion for characters caught in situations not of their own making is bountiful, and from the moment we meet Cary we can feel how her life suffocates her. Ron literally takes her outside, into nature. When the film opens, Ron is trimming Cary’s trees. She invites him to have coffee with her. He accepts. They chat and he trims a branch from the lovely golden raintree that sprouts behind them and grazes at her bedroom window, telling her that Chinese legend says that it can only grow near a house where there is love. Cary likes the story. After Ron leaves, Sirk cuts to a shot of Cary at her dressing table – she has placed the branch in a vase and she gazes wistfully at it as she makes up her face. The branch is her first inkling that another world might exist for her.

Ron returns two weeks later to finish his jobs. He invites her to his place to see the silver-tipped spruces he’s growing. He lives in the greenhouse on a gorgeous piece of land that includes an old mill. He will later turn the mill (with his own manly hands) into a home for them. The mill enchants Cary, she enchants Ron, and they kiss. She tries to resist but fails miserably when he holds her to his strong chest.

Ron reappears in a couple of weeks and invites her to meet his friends Mick and Alida. They live simply and rustically like Ron. At the house Cary discovers a copy of Walden and begins to read: ‘The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation … If a man does not keep pace with his companions perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer.’ Cary thinks it’s beautiful, Alida explains that it is Mick’s bible. Cary asks if it’s Ron’s bible too. Alida explains: ‘I don’t think Ron’s ever read it, he just lives it.’

Later, Ron shows Cary the first round of renovations on the mill and asks her to marry him. She loves him but thinks it’s impossible. He kisses her, enveloping her in his arms and holding her to his chest, saying ‘This is all that matters’. When she tries to plead their case to her selfish college-age children, her son accuses her of not thinking straight: ‘I think all you see is a good looking set of muscles.’ Domestic responsibility and social pressures consume her and Cary walks away from Ron (she’ll eventually return, don’t fret). The music soars. There is nothing wooden about Hudson’s response – he’s all flesh and blood. Hudson has one of the most gorgeous profiles in cinema history and Sirk serves him up to us here, half lit by the silver light reflecting off the snow outside his window, as he bites his bottom lip to ward off tears.

With this role, Hudson’s star persona is aligned with nature and what is natural, and in turn, what is normal. Hudson’s masculinity in All that Heaven Allows is utterly seductive, warm, playful and generous. He’s the kind of man you want to be around, the kind of man you want to fall in love with and move to the woods to be with. I’ve written at length about this film to give those of you who haven’t seen it some sense of Hudson’s enormous appeal as a romantic lead.

For a couple of years after the ill-fated Selznick venture A Farewell to Arms (1957), Hudson’s star waned, until he teamed up with Doris Day for their first collaboration in 1959’s comedy Pillow Talk. With this shift towards lighter fare, Hudson’s star persona developed another layer, teasing audiences with a sophisticated, hypermasculine playboy identity. Two other films together followed – Lover Come Back (1961) and Send Me No Flowers (1964).

Hudson’s acting career is easily defined by these two periods (of course there were many other films, including 1966’s science fiction thriller, Seconds, directed by John Frankenheimer, and a successful television career with his lead role in McMillan and Wife (1971-77), but it’s the Sirk films and the sex comedies that made him a real star).

Similarly, Hudson’s private life has two distinct periods – before AIDS and after AIDS.

Rock Hudson died in 1985 at the age of 59.

The private Rock Hudson was obviously a very different man to the public Rock Hudson that the star machine had worked tirelessly to create.

Does this matter? Yes, but not for the reasons some of the mainstream media suggested when his illness and true sexual identity were revealed. Not because, as they said, he had participated in a life-long deception, had effectively lied to his fans. No. It matters to me because of the way it messes with our ideas about masculinity and homosexuality and the ludicrous idea that who a man sleeps with determines whether he is a ‘real’ man or not.

There is a scene near the end of Lover Come Back where two men, watching Hudson’s character Jerry Webster run through his apartment building dressed in nothing but a woman’s fur coat, express disbelief: ‘He’s the last guy in the world I would have figured.’

When Rock Hudson came out the public voiced the same kind of surprise.

But Hudson didn’t technically come out. He was forced out in July 1985 just ten weeks before he would die on October 2. I can’t find any evidence that he ever personally made a statement to the effect of ‘Yes, I am gay.’ It all started when he appeared on a Doris Day television special and looked shockingly emaciated, slurring his words. Something was very wrong. That large, strong body had changed dramatically and drastically. As his great friend Elizabeth Taylor would later remark, he had turned to ‘skin and bone.’

Not long after, a statement announced that Rock Hudson had ‘inoperable liver cancer.’ But this only led to speculation that something else was wrong when he sought treatment at the American Hospital in Paris and the Institute Pasteur which were then at the forefront of AIDS treatment and research.

Hudson was the first major public figure to announce he was HIV positive. He won’t be forgotten for the courage he showed in this revelation but this shouldn’t be the only thing he is remembered for.

Some say that the body doesn’t lie, that you can’t run away from the reality of the body. And in Hudson’s dilemma there is some truth to this. The ‘truth’ about a closeted man suddenly and uncontrollably became visible and legible on the surface of his body. A body that once signified an ideal of American masculinity – healthy, masculine, heterosexual, normal – now meant something different entirely. HIV/AIDS can be seen as a condition that compels homosexuality to virtually ‘leak out’ of the body. As Richard Meyer has explained with regard to Hudson, it compelled homosexuality to register, ‘Dorian Gray-like, on the surface of his body.’

It’s the surface of Hudson’s body, his manly chest included, which causes confusion and ultimately subverts our ideas of what is normal, of what a ‘real’ man looks like and how a ‘real’ man acts. As Richard Dyer explains: ‘His very stillness and settledness as a performer suggests someone at home in the world … Neither in looks nor in performance style does Rock conform to 1950s and 1960s notions of what gay men are like.’

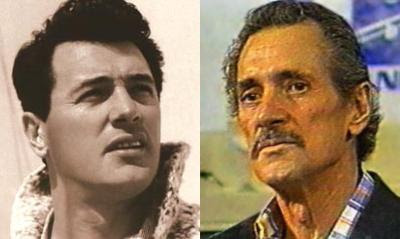

Before (AIDS) and after (AIDS) photos dominated the reporting of Hudson’s illness. Images contrasted strong, healthy, gorgeous Rock with weak, sick and haggard Rock. Several years before he became ill, while shooting McMillan and Wife, his frame had filled out (become puffy, I guess, with middle age and too much booze), which did make the gaunt frame and sunken chest that followed all the more shocking to see.

I’ve been talking a lot about what is considered ‘normal’ – a problematic concept at the best of times – as a way to explain that in the 1950s Hudson’s screen masculinity was considered the norm. One needs look no further than Giant and to contrast his performance with that of his co-star, James Dean. Dean’s Jett Rink is all defensive, nervous shrugs. Hudson upright, square shouldered and still, filling the screen in the same way Gary Cooper did. Dean is emotional, edgy and on the margins; Hudson is contained, solid and part of the mainstream. I think less disbelief would have followed Dean’s coming out if he had done so in his short life (no one is particularly shocked at the possibility that James Dean was bisexual.)

Hollywood promoted the fantasy that Rock Hudson was the ideal American man because he looked like a ‘real’ man – muscular, broad shouldered and square-jawed – and in his films he played them.

But Hollywood’s first hunk was actually queer – an identity positioned outside the mainstream and that despite many steps forward in the last 30 years continues to be isolated from the major narratives of American life.

AIDS literally caused Rock Hudson’s chest to collapse and along with it a certain fantasy about masculinity. It was a fantasy Hudson tried to maintain – first suggesting that he had been exposed to HIV during a blood transfusion after bypass surgery in 1981 and then telling some friends he was anorexic – until it became impossible to do so. The space between his public straightness and his private gayness broke down; his public persona a cultural construction rendered hollow in the aftermath of his diagnosis.

The problem of what we think ‘real’ men look like, sound like and act like is also perniciously bound up with our ideas about what gay men look like, sound like and act like. Much of popular culture continues to insist that gay men are not real men, that the concepts of masculinity and homosexuality are antithetical. Rock Hudson is an interesting actor for me because he shows us that this opposition is simply untrue.

The fragility of Rock Hudson’s chest reminds me of the magnitude of his revelation at the time he made it. In those dark, early days of the AIDS epidemic, gay men were dying at frighteningly rapid rates while dealing with a disease few people understood and most people feared. We take it for granted today, but we should remember that those early days of AIDS forced many gay men out of the closet in the most horrifying way, often with no safety net other than that offered by their community who were all staring into the same abyss together.

There was an enormous chasm between Hudson’s public persona and his private persona, but I’m interested in it not from the perspective of his so-called ‘deceived’ fans but from his point of view. I wonder how truly painful living with this split self must have been for him. I can’t imagine how he felt knowing that the opportunity to finally live openly and honestly had come at such a price. And thinking about this makes me very sad for him. Despite the fame and fortune, it must have been a very difficult life.

If the revelation of Hudson’s homosexuality was a scandal it’s not because of what it said about him, but because of the anxiety it caused the mainstream public. We got it wrong. We didn’t read the signs. And they were there, in a film like Pillow Talk, which played extensively with sexual ambiguity and let Hudson be just a little queer in order to get the girl, and also in Lover Come Back when he says to Doris Day, ‘A kiss? What does that prove? It’s like finding out you can light a stove. It still doesn’t make you a cook.’ Oh no – we can’t pick the ‘real’ men from the others. If a man like Rock Hudson, with that broad chest could be gay, then who else?

His coming out, however it happened, remains a landmark event for the gay community. His position in the conversation about national identity had shifted – the ideas about masculinity bound up in his body would never be the same again.

Hudson must have known his image was collapsing. What we’ll never know is how much this really mattered to him or whether he felt the slightest relief? Some of those close to him have suggested he remained in a state of denial until the end about what was happening to him. Others have said that very few people actually knew he was gay.

Aaron Sorkin, writing for The Huffington Post in 2010, had the following insight:

‘Gay actors, you’ll forgive the expression, are caught between a rock and a hard place … They know that even in 2010, there’s still no such thing as an actor who’s gay, a movie star and alive all at the same time.’

The situation can only have been much worse fifty years earlier.

The closet erected around Rock Hudson’s private, off-screen life was like a prison, but sadly, it also offered him some protection. Hudson must have known he would never have had the diverse and lengthy career he did if this myth was shattered. He lived in a world that didn’t support the idea of a leading man and movie star who was openly gay. And that’s the true tragedy of his life, and ours and Hollywood’s shame.

This is a great post, I really enjoyed reading it!

Thanks Alex, I’m really glad you did. It was enjoyable to write too – always a pleasure to revisit old movies.

my mom and i alwys loved rock hudson and even whe n we found out he was sick it didnt change our feeling s for him.. he was a fine actor… and i imagine a fine person. who i would hve loved to meet. but of course that was not possible…being a regulare person.. just a fan…. we cried alot when we heard the news and felt very sad…. and upset but still loved him and his movies and just deep ly saddened by the whole thing… he was truly a very handsome and talented human being. He would have mad e some gorgeous kids thats for sure. truly a shame to lose him so young. God bless you Roy rest in peac.

It is truly a tragedy, but luckily we always have his movies to remember him with. And he did make a tremendous difference – whether he wanted to or whether he was even aware of it – to the world’s awareness and understanding and action on HIV/AIDS.